This blog reproduces the concluding commentary written by Maryam Niamir-Fuller, Co-Chair of the International Support Group for the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists 2026, to the recent Special Issue of Nomadic Peoples entitled ‘Sedentist Biases in Law, Policy and Practic’, edited by Greta Semplici and Cory Rodgers. The whole issue (and all 2023 content) is published Open Access thanks to our ‘Subscribe to Open’ project for NP.

More than half of land on Earth is rangeland as determined by the latest Rangeland Atlas,[1] consisting of vast areas covered by grass, shrubs or lichens, and sometimes trees. These landscapes support millions of pastoralists and hunter-gatherers, countless plant and animal species, and store large amounts of carbon in their soils.

Rangeland grazing by domestic and wild animals can be sustainable, benefiting both humanity and the planet. Over millennia, pastoral[2] livestock herders have developed, adapted and refined sustainable grazing systems for different ecosystems. Sámi herders raise semi-domesticated reindeer on lichen growing in the tundra. Moroccan shepherds move their animals seasonally between valley and mountain pastures. Sahelian herders graze animals by rotating them across different landscapes and vegetation types, while North American ranchers seasonally rotate their livestock between public and private lands.

Today, scientific evidence provides two important lessons: first, all of these ecosystems have evolved over millennia under the influence of some form of grazing; and second, the more herders move their animals and the more they capitalise on and work with nature’s variability, the more these ecosystems are protected from degradation. Sustainable pastoral grazing is a time-honoured way to maintain livelihoods and food production on lands where crops cannot be grown sustainably.

Emerging evidence vs hidden biases

This is what science tells us today; however, the perception of most policymakers, development practitioners and even some formally educated pastoralists remains largely unchanged since the colonial times – for them, nomadism is an archaic form of livelihood and food production that has to be replaced to meet modern standards. Its replacement is driven by the ‘sedentist bias’ so well described by Rodgers and Semplici and the other articles collected in this Special Issue.

Sedentism has very old roots. Chengis Khan and his nomadic subjects were seen as unruly, dangerous hordes of terrorists who conquered empires. Persian empires were built on the subjugation of pastoralists scattered in the periphery of both territory and society. In the twentieth century, colonialists and the Soviet Union used a new legal system and advanced technologies to do the same.

During the industrial age, the concept of efficiency further strengthened sedentism. It is far more efficient (i.e. cost per benefit to the public) to centralise than to decentralise, to settle than to be mobile, to consolidate rather than disperse. Sedentarisation makes taxation easier. The benefits appeared higher than costs because the costs were transferred to the pastoralists – who have lost access to customary pastures (Undarga), been subjected to burdensome bureaucratic regulations and fees (Grove et al.) or feel forced to settle in order to take advantage of aid and development programmes or land rights but thereby undermine long-standing forms of land governance and livelihood (Hussein et al.; all articles in this Special Issue).

Stephen Sandford coined the term ‘benign neglect’ in the 1980s when talking about how pastoralists were being left behind in development – but some wonder whether that is being too generous. How much of today’s sedentist bias is rooted in an explicit but often disguised aim to subjugate, assimilate and disempower mobile peoples, and how much of it is due to a blindness stemming from ignorance?

Answering this question might explain why the sedentist bias still persists and prevents proper evidence gathering. Rodgers and Semplici in this volume trace the bias in Kenya to the colonial era when the Maasai were restricted to certain areas and isolated, and their movements were curtailed in an effort to prevent transmission of animal diseases. Despite a lack of proper evidence on the impact of mobility on disease transmissibility, public health responses rely heavily on cordons and movement restrictions. How much of this persistence can be explained by the politics of pastoralist subjugation (which then led to the Mau Mau rebellion of 1952–1960)?

Pastoralist-friendly infrastructure, services and legislation

Hassan et al. in this Special Issue argue that the centralisation of social and economic services (health, education, markets) is nothing less than ‘services placed as baits’ to attract pastoralists to settle down. In Tanzania, President Nyerere implemented a ‘villagisation’ programme that attempted to forcibly settle pastoralists around service centres. In the majority of cases, centralisation of services has been a matter of exigency due to lack of funds and trained personnel willing to live in remote areas. This is compounded by a lack of knowledge and awareness that mobility of livestock is beneficial for both land and animal and, if it is to work properly, needs appropriate infrastructure, legislation and services.

Several of the articles in this Special Issue show how the best intentions can fail during implementation because of biases and ignorance.

In 2016 Kenya seemed to be going the right way with the passing of the Community Land Rights Act, since it allowed a community to ‘own’ land. But Hassan et al. show that the implementation of the Act has been influenced by political considerations and a sedentist bias because it has applied legal and procedural state tools (especially the fixing of boundaries) that undermine the flexibility, reciprocity and porousness of land use as required by pastoral mobility in drylands. They also record the pre-emptive sedentarisation that occurs when pastoralists anticipate government-mandated policies. They show how the act of creating fixed boundaries between the communities (meant to secure land tenure) has actually disrupted mobility patterns and created more conflict between pastoralists.

Similarly, the evidence provided by Solimene and Pontrandolfo on the impacts of the EU and Italian government policymakers towards the nomadic Roma/Sinti shows how good objectives (social cohesion and inclusion) can have bad results when they are implemented with a sedentist bias.

The impacts of Covid-19 on pastoralists were quite different from those on sedentary farmers, not because of the disease itself, but because of the policies put in place to contain the disease. Border closures damaged grazing patterns and may have increased livestock disease in northern Kenya and Uganda (Rodgers and Semplici in this volume). One bright spot in Turkana County, Kenya, was that the county government introduced mobile COVID-19 screening units to reach pastoralists.

Livestock identification and traceability systems (LITS) are being imported to Africa from Europe and the USA, and do have some benefits for pastoralists: it is easier to track lost or stolen animals and would allow pastoralists to export their livestock, obtain ‘organic’ labeling, etc.. But what works in theory does not work in practice because of the sedentist bias as pointed out by Groves et al. in this issue. The mandatory implementation of LITS in Namibia has used the tools appropriate for sedentary livestock systems, resulting in added costs to mobile pastoralists (both direct and indirect) such that only richer pastoralists can afford to comply.

Formalisation is an indispensable tool of modern governance, allowing policymakers and development practitioners to devise programmes, leverage funding and monitor impacts. But the tools we use to formalise are geo-stationary. Formalisation in data gathering has meant that mobile populations are either not counted or lumped with settled farmers, and rangelands are counted as ‘dry forests’. The resulting policies and programmes that are enacted leave pastoralists behind, as shown by the UNEP Gap Analysis in 2019.[3] The articles in this issue indicate how collection of geo-stationary data has dispossessed (Hassan et al.) and even criminalised (Groves et al.) pastoralists. The problem is solvable – with a willingness to devise the right indicators and data-gathering tools. Participatory methods for indicator development can, for example, help replace unitary categories of land ownership used as indicators in the sedentist models of land registration, with categories that reflect multiple ownership (reciprocal usufruct, de facto and de jure).

If the root cause of sedentism is ignorance, then the case of the Touareg in Niger (Lunacek in this issue) is some cause for optimism. Despite a high degree of sedentist bias among government, development practitioners and some educated Touareg intermediaries, it is possible to revise not only the content (curricula) but also the structure (mobility and accessibility) of pastoral schools to be more favorable towards pastoralism.

This example and others seem to indicate that the tide is turning. The value of mobile pastoralism has now been embraced by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization,[4] UNESCO has designated transhumance in several countries as Intangible World Heritage, Spain and Senegal have formalised and legally recognised transhumance routes, ECOWAS now issues a transhumance passport in West Africa (although challenges have been recorded), and some countries are experimenting with mobile services for health, education and abattoirs. Many of these examples have been collected by the IYRP Working Group on Land Degradation Neutrality Special Review (forthcoming).

Potential of IYRP 2026 to break the myths and expose the biases

The IYRP aims to raise awareness, break myths and generate new knowledge about rangelands and pastoralists. This Special Issue helps to achieve that by showing how to raise self-awareness about our implicitly held beliefs and biases. Among the IYRP’s many tasks is to show that a mobile pastoral lifestyle and production system is just as fulfilling as a sedentary one, and even better as it can help achieve sustainability for the Earth.

IYRP 2026 is more than a celebration of pastoralists and rangelands. It aims to show the problems and challenges, and yet also give a sense of optimism that more can be done, and that paradigms, common beliefs and mindsets can be changed not just by government officials and development practitioners, but also by the pastoralists themselves.

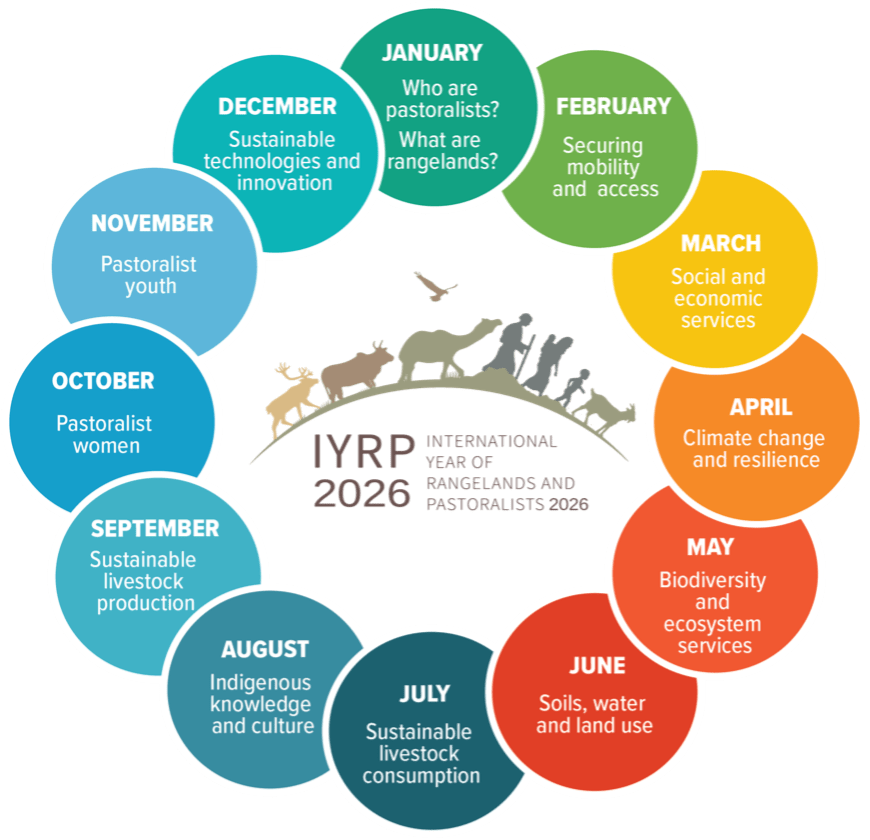

The articles in this issue are addressing many of the twelve Global Themes of IYRP 2026. Border policies (and policies that impose boundaries) impact mobility of pastoralists and their access to rangeland resources (Theme 2); the provision of sedentary services impacts the education, health, economic resources and infrastructure of pastoralists (Themes 3, 8 and 12); and land laws impact mobility, land rights and governance (Themes 2 and 6).

IYRP 2026 is also about generating new knowledge. Much of what we know today about rangelands and pastoralists dates back to the mid-twentieth century. While valuable in retrospective, the old data do not reflect the new realities of pastoralists. Pastoralists and their societies have experienced change, much of it driven by sedentist policies. The community safety net no longer exists for many pastoralists, who are fending for themselves, competing and conflicting between themselves as they try to get the best advantage. Communities, not just individuals, need to be given voices. The value of this Special Issue is in bringing freshly collected new knowledge from pastoralist communities – often difficult to achieve in the current context of lack of funding and of opportunity for field research.

Research gaps

One area of further research could be to identify the best indicators that reflect pastoralism. Even today, we do not have a global standard for rangeland indicators, and most indicators in use have been developed for temperate zones. As explained above, we do not have the right kind of indicator to measure the multiple layers of ownership in pastoralist communities. Many more examples can be given. In 2030, the measurement of the indicators for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will likely not show any improvement for pastoralists, because there were no indicators specific to pastoralism[5] that could be used at the time; the SDGs do, however, provide the opportunity for more research to develop new and more discerning indicators that help close the knowledge gap.

In the USA, fences were originally erected in the Western States around farmland to keep mobile (herded) animals out. As the sedentist bias took hold, the onus and cost of fencing was transferred to the ranchers by requiring them to fence and thus confine the animals. These days, European, American and Australian pastoralists are exploring and rediscovering the value of mobility of livestock. Much can be learnt from exchange of experiences between them and pastoralists in developing countries, as the IYRP 2026 process is showing. Thus, another area of further research could consider how these two types of pastoralists can co-learn to adapt modern services, amenities and infrastructure to the mobility of animals.

Concluding remarks

When I produced ‘Legitimization of transhumance’ back in 1999,[6] I was fighting against the sedentist bias of the twentieth century. I wanted my book to help strengthen the legitimacy of transhumance and pastoralism, not just describe a ‘dying’ system; but there were those in academia and development circles who thought that I was being naïve. Today, I am so happy that they are proven wrong – it is good to see such a strong momentum for protecting and nurturing mobility as expressed in this Special Issue. We don’t have all the answers yet, but pastoralist and other mobile peoples’ voices are gaining strength. Already the campaign to designate 2026 as the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP 2026) by the United Nations has helped spread the word, and I hope the Year’s positive impact will last well beyond 2026.

[1] https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/114064

[2] In this commentary, I use the definition of ‘pastoralist’ that includes nomads, as per the International Rangeland Congress Working Group on Socioeconomic Terms (Kelly et. al. forthcoming).

[3] https://www.unep.org/resources/report/case-benign-neglect-knowledge-gaps-about-sustainability-pastoralism-and-rangelands

[4] https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb5855en

[5] https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-22464-6

[6] Niamir-Fuller, M. (ed.). 1999. Managing Mobility in African Rangelands: The Legitimization of Transhumance. London: FAO and Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics. Intermediate Technology Publications Ltd.