In this blog, originally published as a ‘Snapshot’ in Environment and History (May 2024), Ruby Ekkel investigates Superb lyrebird mimicry and its evolution due to environmental change and human intervention in their habitat. Here, the lyrebird is a multispecies historian, whose imitations provide mediated insights into the changing ecosystems of which it is part.

On 5 July 1931, Australian listeners in all states could switch on their radios to hear the sounds of squawking cockatoos, cackling kookaburras, morose mopoke owls and twittering pilot-birds broadcast into their living rooms. City-dwellers responded enthusiastically, commenting on feelings of intimacy with a geographically distant bush environment. The novel programming by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) was apparently discussed ‘at every turn’ in the following days.[1] One man, whose friends invited him to a shared listening in their home, recalled how the nearby bells of St Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne melded with the layered natural soundscape emitting from the radio.[2] Later, the transmission was conveyed to Tasmania and then, with more difficulty, to Europe and the United States, where it was apparently a ‘hit’.[3] Only one animal, however, was being broadcast over the airwaves: a male superb lyrebird nick-named Joe, who lived in Sherbrooke Forest, Victoria.

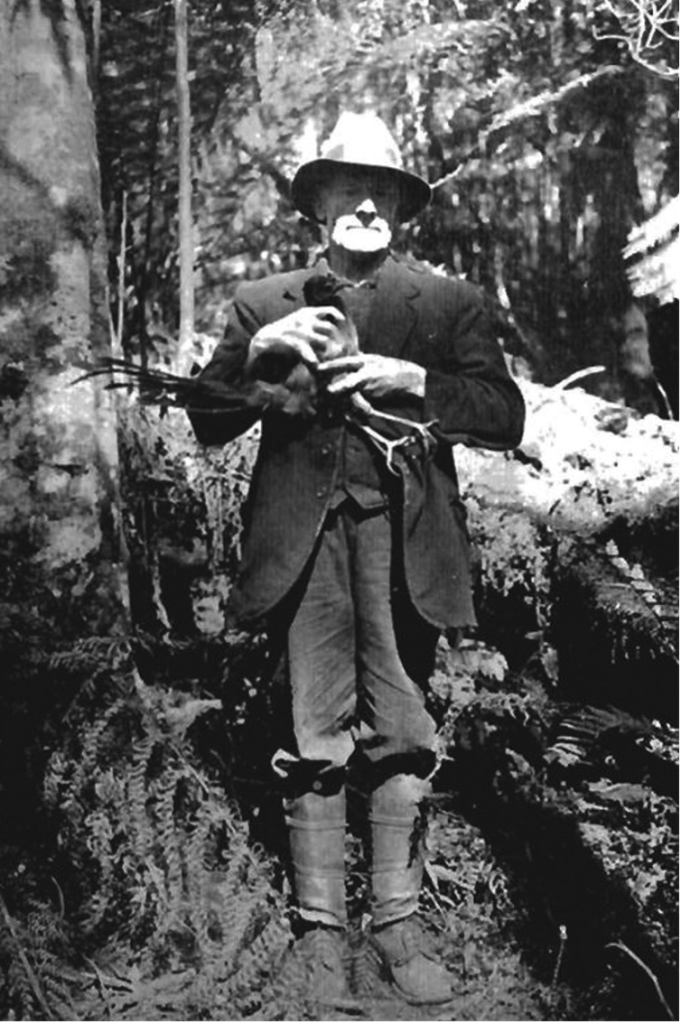

True to lyrebirds’ fame as eerily accurate mimics, the unwitting sensation delivered a selection of his repertoire of thirty-odd imitations of the animals who shared his wet and ferny ecosystem.[4] Joe was enticed to perform within earshot of the bulky microphones (installed with much trouble in the middle of the forest) by way of a mirror, in which he could appreciate his reflection as he sang and danced. Tom Tregellas, who had lived alongside and studied the Sherbrooke lyrebird population for many years, remained nearby, and provided listeners with a soft-spoken commentary on lyrebird nesting habits, in between bursts of mimicry.[5] Joe thus became the first wild Australian bird to be featured in a radio broadcast, a feat that would be repeated a number of times due to popular demand. The breakthrough felt especially sweet to Australian ornithologists and radio enthusiasts alike, because it provided an antipodean rejoinder to the BBC’s historic broadcast of nightingale song in 1924.[6] The ‘wonder songster of the world’ had been successfully shared with the world.[7]

suggests otherwise (Tregellas described her ‘reposing peacefully in my arms’), the

Sherbrooke lyrebirds were indeed relatively comfortable around their long-term visi-

tor. This familiarity allowed him to photograph and record them. The Emu 30 (1931):

plate 44.

Lyrebirds have long inspired human analogies, especially those relating to performance and creativity. White settlers have compared them to ballerinas, poets, opera singers, the Greek hero Orpheus and Aboriginal performers in a corrobboree.[8]One enthusiast insisted in 1933 that the lyrebird was ‘much more completely a person than most of the humans I meet’, and that the ‘aura’ of the species resembled that of Nellie Melba or Anna Pavlova.[9] Indeed, it is difficult to write about the lyrebird without resorting to the anthropocentric terms. In this brief essay, I would like to suggest another analogy: the lyrebird as multispecies historian, whose imitations provide mediated insights into the changing ecosystems of which they are part. I reflect on Joe’s mimicry in the context of emergent multispecies and more-than-human methodologies, considering which lessons the lyrebird may have to offer to historians concerned with conveying co-constitutive environmental relations, the presence of multiple voices and species, and the ethical challenges that arise when we see ourselves as products of an ‘infinitely generative partnership with the things that surround us’.[10]

Scientists have long debated the biological impetus for lyrebird mimicry, and recent research continues to confound consensus.[11] It is believed that greater virtuosity in male lyrebirds has evolved to be a sexually selected trait. Complicating matters is that female lyrebirds also mimic, though less often and perhaps for different reasons, and that birds of both sexes continue to mimic with great vigour outside the mating season and in the absence of other lyrebirds.[12] Tregellas, who lived part-time in a hollow tree-log in order to study Sherbrooke lyrebirds close-hand, concluded that ‘I do not think it is necessary for a hen to be in the vicinity as an inspiration for a male to sing, as he very often calls from what I would think pure joy at the thought of living …’[13] Whether they are performing to attract a mate, to express joy, refine their skills, or simply to show off, lyrebirds’ mimicry can be eerily accurate. Researchers have found that lyrebirds’ shrike-thrush impression (apparently Joe’s favourite), is so accurate that real shrike-thrushes cannot distinguish it from their own communication.[14] In fact, following the 1931 broadcast, the ABC received a number of letters doubting whether a bird could possibly produce such sophisticated imitations, including one requesting that the writer be given a chance to perform on radio: ‘he was sure he was as good a mimic as the man who broadcast the lyrebird calls!’[15]

What has especially astounded observers, then and now, is the lyrebird’s tendency to mimic a number of different sounds at once, creating a coherent natural soundscape or even telling a story. In his popular book The Lore of the Lyrebird, published in 1933, the zoologist Ambrose Pratt enthused about his subject’s ability to ‘reproduce simultaneously an entire concert of sounds without blurring the individuality of any constituent note’.[16] This is an envy-inducing accolade for multispecies historians looking to foreground diversity and relationality while preserving the particular. Lyrebirds often employ this skill to impersonate several bird species at once, as in the ABC broadcast, but they can also evoke less typical milieux. One Sherbrooke lyrebird amazed Tregellas by imitating a complex industrial scene, in which the sound of a charge’s explosion at a nearby stone quarry was mimicked along with the echoing vibrations produced by the explosion in the adjoining hills. He never heard the recitation again, concluding that it was ‘evidently the bird’s piece de resistance’.[17]

As this example suggests, Superb lyrebird mimicry had evolved to convey environmental change due to human intervention in their habitat. The encroachment of white settlers on the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri clan of the Kulin nation, and especially the introduction of logging in Sherbrooke Forest in the 1860s, wrought massive change and destruction for the lyrebirds’ ecosystem. The clearance of scrubby bush relied upon by lyrebirds for nesting, alongside a lively trade in their tail feathers and the introduction of a serious predator in the form of foxes, meant the species was severely endangered by the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1905 the ornithologist A.E. Kitson was despairing:

Thousands of these birds must have sported about this country, making the otherwise rather silent forest a huge natural concert hall. Now, alas! the march of settlement, with its breech-loaders, forest spoilation, and bush fires, has brought about a sad change from a naturalist’s point of view. With the disappearance of the scrub goes the Lyre-Bird, and as the country gets cleared from various sides so patches only of scrubby country are left.[18]

As the sounds of tree-felling, excavation, human voices and barking dogs intruded into the ‘natural concert hall’ of the Dandenong Ranges, the lyrebirds who survived the onslaught added to their vocabulary of impersonation. In 1929 the ornithologist J.A. Leach reported on lyrebirds who could emulate honking cars, puffing trains, saws being sharpened or hacked into a tree trunk, and the ‘series of sounds connected with the falling of a tree including the final crash’.[19]Another Sherbrooke lyrebird, who frequented the home of Edith Wilkinson for many years, impressed observers by mimicking not only the Eastern whip-bird, grey shrike-thrush and golden whistler, but also Edith’s daily greeting of ‘Hullo Boy!’, barking dogs and the yells of nearby woodchoppers.[20] In 1935 they were a little less impressed with his ‘tiresome’ repetition of the sounds of a machine which had recently started crushing rocks for road-building near Edith’s home. [21] Stories like these can of course be exaggerated or invented, but there are sufficient accounts of mimicked logging-related activities that it seems more likely than not that Sherbrooke lyrebirds, faced with an existential threat to their environment, had done what they did best and learned to imitate it.[22]

(GFDL v1.2 licence).

We now know that habitat loss or fragmentation, whether by deforestation, fire or introduced species, can also be reflected in a reduced repertoire of mimicry. Male Albert’s lyrebirds (a closely related Queensland-based species) in disturbed habitats produced fewer imitations and vocalisation types than those in more intact and diverse habitats, with greater access to lyrebird ‘tutors’. Rather than vocalising less often, these culturally bereft birds compensate by producing more repetitions of the same, limited group of imitations.[23] Biogeographers infer that the ‘cultural diversity’ of lyrebird populations may be ‘impoverished by habitat loss and fragmentation in a similar way to genetic diversity’.[24]

Today, evidence of humans’ impact on non-human bodies tends to evoke distaste or distress, like the sea horse nursing a used cotton bud in the deep ocean, or the sperm whale whose bloated body contained a greenhouse’s worth of waste products.[25] The evolution of lyrebird calls to include human elements is generally far more palatable. It can even be delightful, in the unconfirmed case of the individual who reproduced the melodies of a local flautist, and spread an enduring ‘flute-like dialect’ within the region.[26] Nevertheless, like Rebecca Giggins’ ‘world in a whale’, we might imagine the changing Sherbrooke repertoire as a kind of ‘world in a lyrebird’, conveying, with some degree of agency and creativity, historical developments in the multispecies life of Sherbrooke Forest and beyond. The ABC broadcast occurred in a moment when logging had finally ceased in the area and the species was experiencing a boost in nationalistic affection and scientific interest. The lyrebird had become a national icon, a charismatic species separated at least symbolically from other organisms. But Joe’s mimicry conveyed to his radio audience a mediated multispecies account of an inseparably intertwined ecosystem still under threat. It is worth noting as a word of caution that, in 2022, the BCC was forced to admit that the popular 1924 nightingale broadcast which partially inspired the ABC’s version, was fake. When the real songbird could not be prevailed upon to sing for the occasion, presumably frightened by the unfamiliar crew and equipment, a professional bird impersonator stepped in as understudy.[27] This century-long ruse is a reminder of the all-too-human habit of trying too hard to make nature say what we want it to say.

[1] Blanche Miller, ‘The spell of the lyrebird’, Bacchus Marsh Express, 25 July 1931, 4.

[2] H. Stuart Dove, ‘The lyre-bird calls’, Advocate (Burnie, Tasmania), 8 July 1931, 2.

[3] ‘Lyre-bird a “hit” in U.S.A.’, Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 28 July 1931, 10; ‘LYRE BIRD BROADCAST: Unsuccessful experiment’, Daily Advertiser (Wagga Wagga, NSW), 14 July 1931, 4.

[4] ‘Bird calls by radio’, News (Adelaide), 24 June 1931, 3.

[5] Michael Sharland, ‘The lyrebird on the air’, The Emu – Austral Ornithology 31 (2) (Oct. 1931): 146; ‘Tom Tregellas c.1864–1938’, The Emu 38 (3) (1938): 335.

[6] ‘Bird calls by radio: Lyrebird and nightingale on air’, News (Adealide), 24 June 1931, 3.

[7] ‘“Menura”, wonder songster of world: How lyrebird’s melody was captured’, Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 4 July 1931.

[8] ‘Dancing Orpheus (1962)’, Australian Screen, National Film and Sound Archive: https://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/dancing-orpheus/ (accessed 4 Feb. 2024); Philip A. Clarke, Aboriginal Peoples and Birds in Australia: Historical and Cultural Relationships (Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO Publishing, 2023), p. 104.

[9] Ambrose Pratt, The Lore of the Lyrebird (Melbourne: Robertson & Mullens, 1938, first published 1933), 54.

[10] Emily O’Gorman and Andrea Gaynor, ‘More-than-human histories’, Environmental History 24 (4) (Oct. 2020): 713–21; Timothy LeCain, The Matter of History: How Things Create the Past (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 8.

[11] Anastasia H. Dalziell et al., ‘Male lyrebirds create a complex acoustic illusion of a mobbing flock during curtship and copulation’, Current Biology 31 (9) (10 May 2021): 1970–1976.e4, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.02.003.

[12] Anastasia H. Dalziell and Justin A. Welbregen, ‘Elaborate mimetic vocal displays by female superb lyrebirds’, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 4 (34) (April 2016): https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2016.00034/full.

[13] Tom Tregellas (communicated by A.G. Campbell), ‘The truth about the lyrebird’, The Emu 30 (1931): 250. The idea that birds could call for the sheer fun of it was a charged one at the time; the influential naturalist Alec Chisolm was an especially firm believer in avian joie-de-vivre. See Russell McGregor, Idling in Green Places: A Life of Alec Chisolm (North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2019), p. 106.

[14] Anastasia H. Dalziell and Robert D. Magrath, ‘Fooling the experts: Accurate vocal mimicry in the song of the Superb lyrebird, Menura novaehollandiae’, Animal Behaviour 83 (6) (1 June 2012): 1401–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.03.009; H. Stuart Dove, ‘The lyrebird calls’, The Emu – Austral Ornithology 31 (2) (Oct. 1931): 147.

[15] ‘Lyrebird from 5CL next Sunday’, News (Adelaide), 15 July 1931, 2.

[16] Pratt, Lore of the Lyrebird, p. 37.

[17] Tregellas and Campbell, ‘Truth about the lyrebird’, 244.

[18] A.E. Kitson, ‘Notes on the Victoria lyre-bird (Menura victoriae)’, The Emu 5 (Part 2) (2 Oct. 1905): 55–67.

[19] J.A. Leach, ‘The lyre-bird – Australia’s wonder-bird’, The Emu – Austral Ornithology 38 (1929): 209.

[20] Pratt, Lore of the Lyrebird, pp. 24, 28.

[21] Pratt, Lore of the Lyrebird, p. 41.

[22] Logging ceased officially in 1930, and Sherbrooke Forest is now protected as part of a national park.

[23] Fiona Backhouse et. al., ‘Depleted cultural richness of an avian vocal mimic in fragmented habitat’, Diversity and Distributions 29 (1) (Jan. 2023): 109.

[24] Ibid, 115–17.

[25] Alexa Keefe, photographs by Justin Hofman, ‘This heartbreaking photo reveals a troubling reality’, National Geographic, 19 Sept. 2017; Amia Srinivasan, ‘What have we done to the whale?’, New Yorker, 17 Aug. 2020: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/08/24/what-have-we-done-to-the-whale (accessed 3 Feb. 2024).

[26] Hollis Taylor, Vicki Powys and Carol Probets, ‘A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, memory, and narrativity’, Environmental Humanities 3 (1) (2013): 43–70.

[27] Dalya Alberge, ‘The cello and the nightingale: 1924 duet was faked, BBC admits’, The Guardian, 8 April 2022: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2022/apr/08/the-cello-and-the-nightingale-1924-duet-was-faked-bbc-admits (accessed 4 Feb. 2024).

One thought on “Mimicking Lyrebirds in Multispecies History”