This blog by Tomasz Związek on trees as ‘memorial anchors’ was originally a Snapshot in Environment and History (August 2024). The journal is currently seeking pitches for this year’s Snapshots: find out more here.

Trees of my Fatherland! if Heaven grants

Pan Tadeusz, or the Last Foray in Lithuania, by Adam Mickiewicz (1834)

that I return to behold you, old friends,

shall I find you still? Do ye still live?

Ye, among whom I one crept as a child

– does great Baublis still live, in whose bulk,

hollowed by ages, as in a goodly house,

twelve could sup at table?[1]

Trees have lived on our planet for almost 400 million years.[2] For thousands of years they have been an integral part of the cultural landscape, acting as guardians of the landscape by anchoring the narrative of past and present in a metaphysical way.[3] For example, they are said to commemorate great events for a particular community, to remind us of important personalities or, finally, to be a reminder of past economic practices. They can also have a magical meaning. The older the tree is or the more uniquely shaped, the more stories, legends and myths surround it. Trees’ density also plays a role, as a clear distinction should be made between individuals that grow close together in a particular tree stand and those that are solitary and lead a life independent of their forest sisters and brothers.[4] The lone giants in the rural landscape are often the remnants of intensive changes associated with deforestation, cultivation and clearing of fields, domestic animal husbandry or drainage works. The spreading of the crown, the numerous prunings that model the shape of the branches or the notches on the boot are direct traces of the interaction between humans and nature. Another thing is not visible to the vast majority of us, namely that trees record the events of the past within themselves. And I am not writing here about the fact that the system of annual growth rings is a testimony to climate change, prevailing water management in the area or mechanical defects. Rather, the point is that trees also show painful wounds from warfare. We often hear of saw blades breaking on bullets or other metal splinters embedded in the cellulose tissue during a past war when cutting freshly bought wood in carpentry workshops. But they still exist, the trees that have accompanied our daily lives for thousands of years, allowing us to merge more closely with the landscape and tame it.[5] They act as a landmark that, among other things, enables us to build our cultural identity.

It is therefore worth reflecting on how memorial anchors were built with trees in diverse places and at different times, and why people favoured certain objects and gave them an extraordinary significance that distinguished them in the surrounding landscape. How they were entrusted with the task of guarding the landscape, which (according to original intentions) was to be long-lasting and transcend time. At this point, it should also be emphasised that this function is important in that human lifespans are nowhere near those of trees and the dynamics of growth, maturity and ageing here are definitely to our – human – detriment.

* * *

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, information about the felling of a large Lithuanian oak caused great excitement in the Polish and Lithuanian regions.[6] The tree grew on the land of Dionysius Paszkiewicz (1757–1830), a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman who lived on the Borda estate in Samogitia.[7] This oak tree called Baublis[8] delighted all visitors to the estate with its size, but in 1812 the owner of the estate decided to cut it down.[9] After it was felled, the annual rings were counted and its age was estimated at more than 700 years. This means that its youth coincided with the formation of the early medieval Lithuanian state, while its further fate was closely intertwined with the complex processes of establishing the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the growth of this political formation and its partition by neighbouring states in 1772 to 179. It can be said that in the fate of the tree lay a metaphor for the fate of the state and the nation, which grew and went through stages of youthful rebellion and maturity. The death of the tree, in turn, allegorically expressed the death of the Polish-Lithuanian state and the longing for the lost state – hence Baublis is mentioned by Adam Mickiewicz, among others, in his poem entitled ‘Pan Tadeusz’.

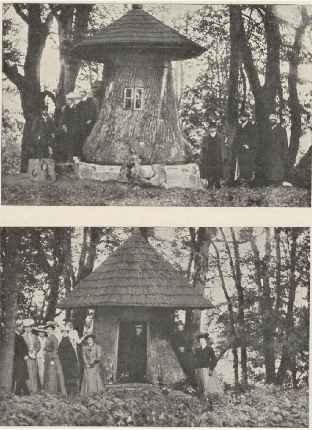

After the beheading, Baublis was divided into three parts. Paszkiewicz made an arbour from the lower part (Figure 1), while the middle part was given to the then Bishop of Samogitia, Joseph Anrulf Giedroyć. Two wide planks were made from the rest of the tree. The aforementioned pavilion was a place where the owner of the tree collected various archaeological objects that he found in his neighbourhood. He also engraved all kinds of poems in it. Baublis became particularly important during the Napoleonic era, when Paszkiewicz’s estate was visited by soldiers. He wrote: ‘Soldiers from different countries visited my house and saw an oak tree standing right there, they looked at it and all left with respect, assuring me together that they had not seen an oak tree of similar size in their countries – which were warmer than ours.’[10] Baublis was a creation ahead of its time. It was a monument to nature that combined museum and patriotic aspects and its overtones were not understood by many people of the time, who marvelled at the Lithuanian nobleman’s actions.[11] It was suggested he build an altar there, convert the pavilion into a food shelter or cut wood for the planks of the well. As Paszkiewicz himself wrote: ‘In a word for different things, my oak was assigned, and I answered everyone with silence’.

* * *

The period of the loss of Polish statehood between 1795 and 1918 was a time of intensified attempts to build and consolidate patriotic attitudes. Due to the difficulty of building common memory in urbanised areas, which were particularly subject to the influence of the partitioners, the onus on forming patriotic attitudes shifted to rural areas.[12] It is therefore not surprising that, after the restoration of independence at the end of the First World War, various types of figures and events that were important for collective memory began to be associated with monumental trees. One of hundreds of examples of this is the pine tree under which the hero of the 1794 uprising against the Russians – General Tadeusz Kościuszko – was to rest before the Battle of Maciejowice. This pine tree is still called Kościuszko’s Pine and stands by the road a few kilometres from the village of Maciejowice (Figure 2). As a result of a local government initiative in 1924, this tree was surrounded by a low fence and an inscription was placed at its base. Remarkable is the presence of a shrine on the tree itself (which is no longer preserved today). Such an object was directly related to votive and thanksgiving purposes, but – even today – has a protective function, preventing the tree from being cut down. Today, the Kościuszko Pine is filled with concrete from the inside due to its progressive decay (Figure 3). Its form, structure and anchored memory have been fixed despite death, like the mask of Agamemnon, and it has become what could be called a zombie tree. In addition, it has been given a new patriotic framework that emphasises its uniqueness.

It is worth considering the spatial context and the structure of the tree. This pine certainly grew in solitude or in a relatively loose community in the early nineteenth century, because the trunk of is twisted. It is common for the fibres to twist when an individual suffers from a genetic disease or grows in an open area exposed to the wind.[13] This pine tree grew in a woodless area in the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth century, as evidenced by preserved cartographical material. This would also explain its size, and its unusual shape. In connection with its location on one of the roads leading from the north to Maciejowice and the context of the past events that took place in the vicinity, this tree must have played a dominant role in the landscape, such that one could easily attribute to it a story related to a national hero. The pine tree reinforces the votive character of the site by complementing the sacred sphere emphasised by the presence of the shrine.

* * *

The custom of tying the memory of historical events to natural monuments such as trees has deep cultural roots, as trees have been a representation of supernatural powers for centuries.[14] Their longevity and monumentality have allowed their history to be linked to political and social events, especially in the last 200 years. Trees dominate the open landscape and act as a very important element around which the memory of certain communities is anchored, linking the traditions of the past with the present and future.

* Research on this issue was founded by Polish National Science Center (NCN) grant entitled ‘Anthropogenic transformations of the environment in the context of modernization processes of the Congress Poland’ (no. 2022/47/D/HS3/02947). I would like to kindly thank Szymon Jastrzębowski, Robert Piotrowski and Karolina Ćwiek-Rogalska for their valuable comments on this essay.

[1] Adam Mickiewicz, Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania, transl. by G.R. Noyes (London-Toronto, 1917), p. 90.

[2] W.E. Stein et al. ‘Mid-Devonian Archaeopteris roots signal revolutionary change in earliest fossil forests’, Current Biology 30 (2020): 421–31.

[3] R. Caramiello and P. Grossoni, ‘Monumental Trees in Historical Parks and Gardens and Monumentality Significance’, in G. Nicolotti and P. Gonthier (eds), The Trees of History. Protection and Exploitation of Veteran Trees. Proceedings of the International Congress. Torino, Italy, April 1st—2nd 2004 (Torino, 2004), pp. 3–8.

[4] Cf. K. Ćwiek-Rogalska, ‘Haunted vegetation: Formerly German orchards in Polish Pomerania’, Environment and History 30 (1) (2024): 3–12.

[5] O. Jones and P. Cloke, Tree Cultures: The Place of Trees and Trees in Their Place (London: Blackwell Publishing, 2002), p. 40.

[6] D. Paszkiewicz, ‘O dębie mającym przeszło lat tysiąc zwanym Baublis, który jest na Żmudzi w majętności Bardzie należącej do Dionizego Paszkiewicza’, Sylwan 1 (1827): 99; and M. E. Bernsztajn, Dionizy Paszkiewicz, pisarz polsko-litewski na Żmudzi (w pierwszej połowie XIX wieku) (Wilno, 1934), pp. 13–14.

[7] Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, vol. 1 (Warszawa 1880), pp. 107–08.

[8] The name comes directly from the Lithuanian language and could mean a bird (Botaurus stellaris) or derive from the verb ‘buzzing’ or ‘roaring’. See more in U. Bijak, ‘Arboretum onomiczne’, Onomastica 61 (2) (2017): 385.

[9] Paszkiewicz, ‘O dębie mającym przeszło lat tysiąc’, 101.

[10] Ibid., 106.

[11] Cf. G. Mickūnaitė, ‘Imagining the real: Mental evidence and participatory past in nineteenth-century Lithuania’, in J.M. Bak, P.J. Geary and G. Klaniczay (eds), Manufacturing a Past for the Present: Forgery and Authenticity in Medievalist Texts and Objects in Nineteenth-century Europe, pp. 267–86; and D. Katinaitė, ‘First Lithuanian museum – Baublys in Dionizas Poška’s garden’, Opuscula Musealia 27 (2020): 117–30.

[12] K.J. Jędrzejczyk, Tożsamość narodowa społeczeństwa polskiego po okresie zaborów. Rozważania na przykładzie archeologii w Polskim Towarzystwie Krajoznawczym w latach 1906–1950 (Włocławek 1950), p. 33.

[13] Cf. L. Eklund and H. Säll, ‘The influence of wind on spiral grain formation in conifer trees’, Trees 14 (2000): 324–28.

[14] H. Galera, Morfologia a symbolika, p. 126.