In this blog, originally published as the ICEHO pages in Global Environment 17.3 Jonatan Palmblad advocates for a renewed scholarship of synthesis – the ability to bridge theory and practice, history, present and future – and even the physical and the metaphysical

It was the Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana who observed that ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’. Frequently invoked, if often unattributed, this aphorism gives credit to the work of historians even in times when usefulness is commonly equated with innovation and invention. Still, Santayana’s pithy phrase begs an important question: what is there to learn from history, other than what not to do? Though circumstances have changed since he wrote in the early twentieth century, I would argue that earlier, even long-neglected, approaches, ideas and critiques can still help our engagement with the present and shape the future – that they constitute a ‘usable past’.[1]

All historians know that thinkers and ideas are influenced and circumscribed by the contexts of their times. Sometimes, then, it is helpful to adopt what Friedrich Nietzsche called ‘untimely’ (unzeitgemäße) ways of thinking – or to get ‘unstuck in time’, as Kurt Vonnegut had it.[2] In other words, there can be benefits in treating the arguments and commitments of earlier scholars as potential sources of insight into current concerns. At the very least, this prompts us to consider the affairs and problems of the present from a different angle, and it would be remiss to rule out the usefulness of such perspectives in advance.

Here I want to speak a word for the scholarship of synthesis – a form of interdisciplinarity that preceded the widespread use of the term, but that was largely shouldered aside by enthusiasm for the endless promise of scientific research after World War II. ‘This is an era of specialists, each of whom sees his own problem and is unaware of or intolerant of the larger frame into which it fits’, wrote Rachel Carson in 1962.[3] Synthesis resists and overcomes this still escalating fragmentation of knowledge – a hallmark of late modernity – and, at this conjuncture, when the idea of interdisciplinarity is widely embraced but there is little consensus about what it is and how it can be achieved, historical synthesis offers a fine example of the insights to be gained from the broad-ranging integration of disciplinary knowledges and approaches.

The American public intellectual Lewis Mumford (1895–1990) exemplifies the practice of scholarly synthesis.[4] A mid-twentieth century ‘Renaissance man’, and a remarkable scholar who taught at MIT and other prestigious universities without so much as a bachelor’s degree, Mumford’s curiosity ranged across almost all known subjects, without losing sight of how they relate to one another.[5] A voracious reader, he was also a prolific writer, and through eight decades (between the 1910s and the 1980s) he published over a thousand works. Mumford was moreover a prominent public intellectual, whose career turned on his youthful conviction that modern society was heading towards ecological and social disaster. Looking back at his work in old age, he characterised his own thinking as ‘ecological’, invoking both the discipline of ecology and what he believed to be the fundamental interconnectedness of ideas and subjects – with each other and with the world itself.[6]

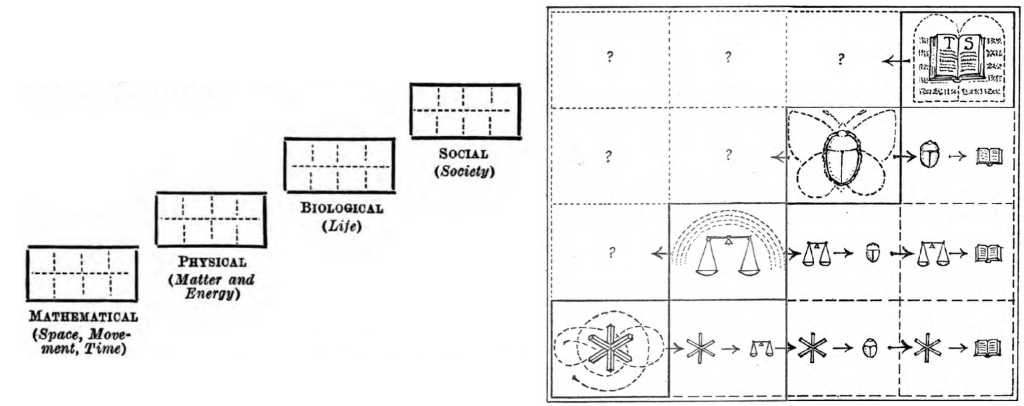

Just as Mumford described the polymath George Perkins Marsh’s Man and Nature (1864) as the fountainhead of the conservation movement, Mumford might be considered one of the wellsprings of environmental history.[7] Marsh used history to describe the increasingly dysfunctional relationship between western civilisation and the natural world, and Mumford conducted similar critical work from an even more multi-faceted perspective, generally considering physical, ecological, technological and social environments together. Mumford’s was not just a generalist scholarship that resisted the growing tendency towards specialisation; it was methodologically rooted in the idea that human–environment interactions can only be understood properly through an interdisciplinary outlook. This idea was itself historical and came from his eclectic mentor, the Scottish biologist and sociologist Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who had sought to synthesise science and knowledge to improve the human environment – and who had introduced Mumford to Marsh’s work in 1920.[8] Both Geddes and Mumford believed that a historical understanding of wide ecological regions, which took ‘natural’ and social factors into account, was necessary for the democratic planning of cities. Though Geddes was simultaneously more practical and theoretical than his acolyte, Mumford expanded his mentor’s gaze beyond the region of immediate concern. If Geddes regarded the history of human–environment interaction as an aid to good town planning, Mumford used what we now call environmental history to better understand human civilisation and its challenges. This has been acknowledged by some. For example, Ramachandra Guha argued three decades ago that Mumford’s Technics and Civilization (1934) and The Culture of Cities (1938) ‘need to be read as essentially ecological histories of the rise of modern Western civilization’.[9] Indeed, these and many of Mumford’s other works deal with how the ‘West’ became ecologically, socially and economically unsustainable.

Mumford was both more and less than an environmental historian, because he avoided a resolute focus on ecological concerns in order to relate such problems to other factors in history. This generalist perspective led him to understand history in terms of complexes: socio-techno-environmental wholes in which humans, ideas, resources, landscapes, techniques and tools interact.[10] This is not the only way one can do environmental history, but these ‘complexes’ come close to what leading American practitioner John McNeill has dubbed ‘clusters’ – ‘new combinations of energy sources, machines, and ways of organizing production’.[11] Such a way of thinking is ‘holistic’ in that it considers the larger and paradigmatic wholes in which the phenomena of everyday life are situated.[12] This approach does not preclude the study of phenomena in their own right; instead, it offers a broad context that includes consideration of ideas, ideology, knowledge and discourse. So, ideas are engaged without ignoring the material and ecological worlds in which they are situated – while cultural and ideological environments are recognised as essential aspects of the human environment. In sum, Mumford’s ‘complex’ contextualisation offers a useful theoretical ‘tool’ for thinking about the environmental past.

Mumford’s oeuvre also points, usefully, to the importance of giving knowledge practical value. Advocacy and activism are important goads towards the systemic changes needed to address the biodiversity, climate and other crises that loom so large today. Crucially, however, environmental historical expertise can also help by illuminating paths towards the realisation of more just and sustainable futures for all planetary life. Mumford learned the importance of planning from his Scottish mentor and adapted Geddes’s ‘regional survey’ method to map out the spatial and temporal contexts of cities and towns while seeking to identify ways of improving lives lived within them. This required synthesising research from many disciplines, including history,[13] and Mumford, a committed ‘generalist’, typically undertook this integrating work himself.[14] Many environmental historians have followed his lead, but relatively few have emphasised the practical utility of their synthesising endeavours. Environmental historians are the obvious inheritors of Mumford’s elaboration of regionalism, that sowed the seeds of what is now more aptly called bioregionalism and of the task that Geddes assigned to sociologists: coordinating and synthesising knowledge on socio-ecological regions.[15] Though the term gained credence long after his passing in 1990, Mumford’s relevance to discussions of the ‘Anthropocene’ is also worth considering. Regardless of earth scientists’ doubts about the Anthropocene as a geological epoch, the idea marks undeniable anthropogenic processes of earth transformation. Still, questions remain about how this epoch came to be and how to ensure survival through the changing circumstances it will entail. Almost a century ago, Mumford was building on the prescient work of G.P. Marsh to argue that western civilisation was undermining its ecological foundations. Rather than simply pitting ‘man’ and ‘nature’ against each other, however, Mumford emphasised how all-too-powerful technologies and narrow understandings of science and knowledge are central to the problems of planetary survival. In Mumford’s view, the material means at the disposal of modern humans, and the ideological ends we strive for – such as growth, control, and expansion – were (and are) both essential components of the ecological crisis. In his last academic works, Mumford coined the term ‘megamachine’ to describe the current paradigmatic complex of social organisation, ideas and technology. To effectively resolve the ecological crises that he saw developing through his final years, he argued the need to rethink technology altogether. In a nutshell, Mumford aspired to change modern societies’ relations to the world by the embrace of new technologies informed by older, less devastating practices and attitudes as well as by organic life itself. This approach surely demands deep knowledge of history and the humanities – making these attributes more germane than ever.[16]

The humanities have a key role to play in assessing, limiting and changing the terms and implications of our present conjuncture, and following Mumford’s lead by thinking historically across disciplines will – I believe – facilitate the necessary discussions between specialists. For example: neither modern global society nor today’s ecological crises would exist without humanity’s increasingly powerful tools and layered social organisation, and Mumford’s theory of the ‘megamachine’ anticipates contemporary technological explanations of the Anthropocene such as the ‘technosphere’, the ‘Technocene’ and even the ‘Capitalocene’. These concepts and much recent work in Science and Technology Studies have extended and refined Mumford’s focus on socio-techno-environmental complexes, but his synthesising framework and plain-language arguments retain (and increase) their value as the Anthropocene concept fragments and understandings of the crisis are shrouded by fast-proliferating specialist terminologies.[17] The nature of the Anthropocene demands synthesis, both for understanding its complexity and for amassing the joint effort needed to thwart the destructive processes behind it.

Environmental historians will hold disparate views of Mumford’s work. Some will find it fascinating and useful; others will be dismissive. Not everyone wants (or needs) to wrestle with deep cultural explanations of the ecological crisis. Not everyone wants (or needs) to be highly interdisciplinary. Not everyone wants (or needs) to articulate practical solutions to pressing problems. And that is fine. As John McNeill has indicated, ‘Usefulness in the context of today’s problems should not be a requirement for historians’. Environmental historians do not have to be useful – but there are many opportunities for those who so wish to be just that.[18] Conversely, some students of contemporary crises might find that earlier engagements with similar issues are of marginal value. Why go back, they might ask, to old notions and thinkers, when we now have so many new ideas and perspectives? Certainly we are now overtly conscious of much that earlier scholars ignored – especially issues of Indigeneity, feminism, colonialism and social and environmental justice. Yet it is also fair to note that much inclusive and theoretically advanced research – although of great import – seems to have little impact on the biogeophysical and social crises of our times. We understand, now more than ever, just how deep, threatening and inequitable the causes and consequences of these crises are, but they and the processes that underlie them keep escalating. Perhaps, then, it is time to set aside the hubris of high modernity, to acknowledge the wisdom of the elders by adding the best and most pertinent ideas and perspectives of earlier scholars to our ever-developing ‘toolbox’ of environmental-historical inquiry.

Knowing the use and limitations of conceptual tools makes it possible to bring the past alive without regressing into reactionary and naive nostalgia; to remain critical of the past without discarding what is useful and needed; to apply and refine integrative approaches that specialised research has rendered obsolete from its own fragmented vantage point. This certainly applies far beyond the specific case of Lewis Mumford, important synthesiser though he was. In history, there is no lack of voices forgotten, neglected, ignored, silenced and oppressed – and many of these voices still have much to say![19] As Indigenous Brazilian Kayapo scholar Kaká Werá suggests, the increasing loss of ancestral knowledge of our own naturalness might be the very root of the ecological crisis.[20] History may help to avoid the repetition of failures, as Santayana had it, but it is also replete with positive, critical and imaginative ideas that we need to engage and build upon. In particular, I would argue that those who put synthesis and wholeness first – rather than analysis and specialisation – have fertile seeds from which to grow the understanding needed to address our current socio-ecological dilemmas, and that historical critiques and solutions provide rich soil in which they might thrive. The scholarship of synthesis can help us better understand how we ended up in our current situation and guide our engagements with the present. As such, it is one of history’s most valuable resources – and an essential feature of environmental history’s usable past.

Jonatan Palmblad is Senior Editor at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, LMU Munich, and holds a Dr. des. degree in Environmental Humanities. He is a communicator for the European Society for Environmental History (ESEH) and the International Consortium of Environmental History Organizations (ICEHO), and together with Jessica DeWitt he recently published a chapter on the communication of environmental history in The Routledge Handbook of Environmental History (Routledge, 2023).

Email: Jonatan.Palmblad@rcc.lmu.de

[1] This notion I borrow from the literary critic Van Wyck Brooks, who over a century ago believed that paths not taken (and thus not part of Santayana’s narrow conception of history) could be mobilised to change the future. V. Wyck Brooks, ‘On creating a usable past’, The Dial (11 April 1918): 337–41.

[2] Nietzsche is a good example of a historical person with highly problematic views who nevertheless provides tools for critical thinking acknowledged across the political spectrum to this day. E.g. F. Nietzsche, ‘On the uses and disadvantages of history for life’, in Untimely Meditations, trans. R.J. Hollingdale (Cambridge: Press Syndicate, 1988), pp. 57–124. Vonnegut’s phrase is from Slaughterhouse-Five, in which his alter ego revises the 1960s narrative of the Dresden bombing.

[3] R. Carson, Silent Spring (London: Penguin Classics, 2012), p. 12.

[4] The ecological aspects of Mumford’s thinking have been investigated in R. Guha, ‘Lewis Mumford: The forgotten American environmentalist: An essay in rehabilitation’, Capitalism Nature Socialism 2 (3) (1991): 67–91; M. Luccarelli, Lewis Mumford and the Ecological Region: The Politics of Planning (New York: The Guilford Press, 1995); J. Biehl, Mumford Gutkind Bookchin: The Emergence of Eco-Decentralism(Porsgrunn: New Compass, 2011); B. Morris, Pioneers of Ecological Humanism: Mumford, Dubos and Bookchin (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2017).

[5] For an overview of Mumford’s ‘generalism’, see G.V. Beckwith, ‘The generalist and the disciplines: The case of Lewis Mumford’, Issues in Integrative Studies 14 (1996): 7–28.

[6] See the interview with Mumford in A. Chisholm, Philosophers of the Earth: Conversations with Ecologists (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1972), pp. 2–4. It is in this broad sense of the term ‘ecological’ that we must understand Mumford’s famous phrase that ‘All thinking worthy of the name now must be ecological’. L. Mumford, The Myth of the Machine, vol. 2, The Pentagon of Power (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 393.

[7] G.P. Marsh, Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003); L. Mumford, Sticks and Stones (New York: Boni and Liveright, 2024), p. 201; L. Mumford, The Brown Decades: A Study of the Arts in America(New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1931), pp. 72–80. Mumford cited Marsh also in other works, and in 1955 he organised an international and interdisciplinary symposium, with geographer Carl Sauer and entomologist Marston Bates, in honour of Marsh. See W.L. Thomas, Jr. (ed.), Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1956).

[8] For the introduction to Marsh’s Man and Nature, see P. Geddes to L. Mumford, 13 Nov. 1920, in Novak (ed.), Lewis Mumford and Patrick Geddes, p. 80. Geddes was familiar with Marsh already in the late 19th century; see P. Geddes, ‘The influence of geographical conditions on social development’, The Geographical Journal 12 (6) (December 1898): 580–86, at 581. For an outline of how he understood the relationship between the sciences, see P. Geddes and J.A. Thomson, Biology (Williams & Norgate, Ltd., 1925), pp. 136–85.

[9] Guha, ‘Lewis Mumford: The forgotten American environmentalist’.

[10] J. Palmblad, Prometheus rebound: Lewis Mumford, the ecological crisis, and the return to reality (Ph.D. Thesis, Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, 2023). For his understanding of complexes, see especially L. Mumford, Technics and Civilization (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1934).

[11] McNeill’s conception of ‘energy regimes’, paradigmatic examples of clusters, resemble what Mumford understood as phases of ‘technics’ (e.g. paleotechnic, neotechnic, biotechnic phases). See J.R. McNeill, Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World (New York: W.W. Norton & Norton, 2001), pp. 296–97. Mumford also emphasised the ideological components of such constellations. This is a key idea in Mumford, Technics and Civilization.

[12] One might perhaps think of these also as ‘assemblages’ or what Michel Foucault called a ‘dispositif’ (sometimes rendered as ‘apparatus’ in English), though there are many understandings of these terms.

[13] See especially P. Geddes, Cities in Evolution (London: Williams & Norgate Ltd., 1949); and V. Branford, Interpretations and Forecasts: A Study of Survivals and Tendencies in Contemporary Society (New York and London: Mitchell Kennerley, 1914).

[14] Apart from his work as a member of the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA), Mumford also published planning proposals. E.g. L. Mumford, Regional Planning in the Pacific Northwest: A Memorandum (Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Council, 1938); L. Mumford, Whither Honolulu? (Honolulu: City and County of Honolulu Park Board, 1938).

[15] For a conceptually similar approach within environmental history, see V. Winiwarter and M. Schmid, ‘Socio-natural sites’, in S. Haumann, M. Knoll and D. Mares (eds), Concepts of Urban-Environmental History (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2020), pp. 33–50. On bioregionalism, see also K. Sale, Dwellers in the Land: The Bioregional Vision (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1985); M. Carr, Bioregionalism and Civil Society: Democratic Challenges to Corporate Globalism (Vancouver and Toronto: UBC Press, 2004); B. Taylor, ‘Bioregionalism: An ethics of loyalty to place’, Landscape Journal 19 (1–2) (2000): 50–72.

[16] The idea that we must rethink technology is clearly expressed already in Technics and Civilization, but his final rendition of the argument was that a ‘biotechnics’ had to replace the current ‘megatechnics’ as the prime mode for organising human societies. See especially the two volumes of The Myth of the Machine. For a similar idea, see the notion of ‘intermediate technology’ in E.F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered (Tiptree: The Anchor Press, 1973), pp. 143–44.

[17] The many neologisms and alternative notions to the Anthropocene have, in the words of Helmuth Trischler, served as a ‘trading zone’ for ideas, but, if humanity’s ecological crisis is to be resolved, these disparate explanations and theories must become complementary rather than competing. See H. Trischler, ‘The Anthropocene: A challenge for the history of science, technology, and the environment’, NTM: Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin 24 (3) (2016): 309–35.

[18] J.R. McNeill, ‘The uses of environmental history’, Seeing the Woods, 1 March 2017. https://seeingthewoods.org/2017/03/01/the-uses-of-environmental-history (accessed 1 April 2024). On how to think about environmental history and socio-ecological usefulness, see J. Palmblad and J. DeWitt, ‘Communicating environmental history’, in E. O’Gorman, W. San Martín, M. Carey and S. Swart (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Environmental History (London: Routledge, 2023).

[19] For example, Janae Davis and colleagues argue that, to deal with the Anthropocene crisis, ‘we must recognize the numerous Black, Brown, and Indigenous peoples who have, for many years, advanced non‐binary conceptions of the human–nonhuman relationship’. J. Davis, A.A. Moulton, L. Van Sant and B. Williams, ‘Anthropocene, Capitalocene, … Plantationocene?: A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises’, Geography Compass 13 (2019): e12438.

[20] K. Werá, ‘Para onde podemos caminhar?’, in K. Werá and R. Kleinubing (eds), Oboré: Quando a terra fala (São Paulo: Tumiak Produções, Instituto Arapoty, 2022), pp. 36–44. On this topic, I also recommend Célia Xacriabá’s chapter in the same volume.