In this blog, originally published as an Environment and History ‘Snapshot’ in August 2024, Dimitrios Bormpoudakis uses the case of forced exile in Greek islands to illustrate how ecologies of displacement matter in adapting to climate change.

‘Narratives of the [past] matter in climate adaptation’.[1] Following this cue, I argue that environmental histories about displacement matter in adapting to climate change. I use the case of the forced exile of people to Greek islands in the mid-twentieth century to illustrate the provocation that ecologies of displacement can help us better understand how to navigate an essentially new world. Drawing from the memoirs, objects and poems created by the exiles, I (re)tell the story of how non-human natures were part of the ecologies the displaced produced to rework, resist and survive their displacement. This (re)telling, I argue, is crucial in an era marked by inevitable and increasing non-human unfamiliarity.

Non-human nature is steadily, albeit unevenly, becoming unfamiliar. Climate change is creating unfamiliar climatic and environmental conditions for humans and non-humans alike. The latest IPCC report (2022)[2] states with ‘high confidence’ that ‘climate change has already disrupted human and natural systems’ and exposed them to ‘conditions that are unprecedented over millennia’, leading to increasingly ‘unfamiliar’ climate patterns.

In my reading, the environment-displacement nexus is typically understood negatively: the environment (or nature, or the landscape, or forests, etc.) are either negatively impacted by the displaced or lead to – negatively construed – displacement (e.g. climate refugees). I argue here that understanding the ecologies of displacement enacted in Greece after World War II as plural, can help move beyond this negative view and provide clues into climate adaptation and mitigation.

Ecologies of displacement in Cold War Greece: the ‘light of day was our comrade’

Everything was a mystery. Night, dark, unfamiliar[3]

Starting in the interwar years, and extending up to the fall of the Colonels’ Regime in 1974, the exile of dissidents to remote and/or desert islands took on an unprecedented magnitude during the Greek Civil War (1946–1949), with c. 50,000 passing through Maksonisos island alone. These tens of thousands of people were resistance fighters (as members the National Liberation Front), members of their families, communists and communist sympathisers, men and women, young, old and children, rural and urban, educated and illiterate.

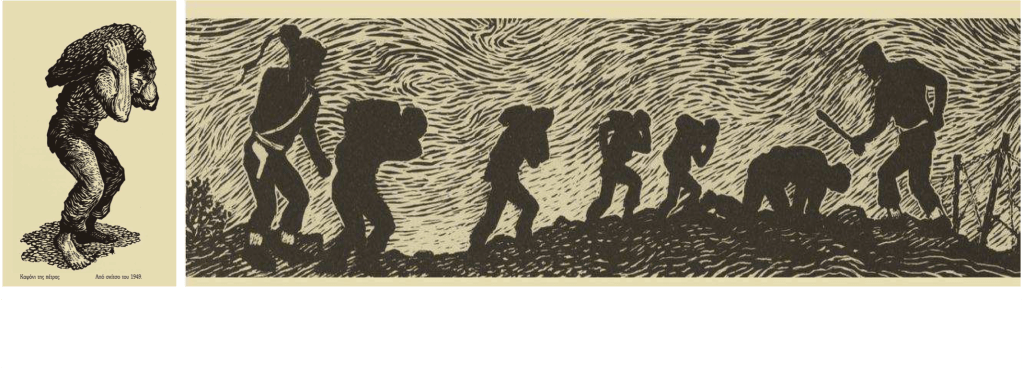

For Greek historiography on displacement, non-human nature has predominantly hostile implications: ‘the elements of nature become antagonists, oppose, pose a threat to humans’.[4] This scholarship to a large extent reflects the reality of exiled lives. The carrying of stones, the cold sea, the blazing sun, insects, rats, cats, snow, the night and many other elements of nature were used as the medium through which the displaced were tortured in the island camps.

Nevertheless, there is another angle in the relations enacted between non-human nature and the exiles: where the ‘elements of nature’ were used mediums of confinement, hardship, mental and bodily torture, they were also used as mediums of collective and individual oppositional ecologies of displacement in unfamiliar and hostile environments. As I will show, it is precisely this unacknowledged plural aspect of the ecologies of displacement that can provide some insights into adapting to, resisting and reworking climate change and its multiple impacts.

While the torturers were in ‘satanic alliance with nature’,[5] the displaced also displayed individual and collective agency with non-human nature too. To read Helias Staveris write it about, the displaced found a ‘comrade’ in non-human nature, in direct opposition to their torturers:[6]

Our friend and comrade [sindrofos] remained firmly the light of day. Under the sun, we faced everything better. And every day as soon as it dawned, Dikeos, turning towards the Military Policemen [alphamites], would shout: ‘Come on you alphamite whores, now, under the light of day, let’s settle this!’

The use of the word ‘comrade’ by a communist in Civil War Greece to address an ‘element of nature’ is crucial here. The term ‘comrade’ is a mode of address that can transcend individual identities and differences, a call to action that emphasises a shared commitment (with nature!) in the struggle for achieving common political goals.[7]

But it was not just the ‘light of day’ that was a ‘friend and comrade’ of the exiles. In the song ‘Our dog, Dick’ (based on a poem written by exiled poet Yannis Ritsos), Dick, ‘our friend’, was living with the displaced in Lesvos island.[8] Dick would bark when police guards approached and that way would reveal their presence to the exiled. So, the police decided to kill it. A former exile wrote years later: ‘We saw him as a fellow prisoner … He too lived as an exile. He lived our lives’[9]

Upon arriving in these unfamiliar islands, the exiles started building sense(s) of place using the materials they found at hand (Figure 2). Island floras were among the things that the displaced employed. In March 1950, Yiannis Ritsos sent a poem in a letter from Makronisos to a friend on the affective atmosphere a bouquet of flowers was creating in his tent. He wrote:[10]

Look at the chamomiles with their little white lantern all lit – crawling on the rocks – on the beach – strange – in this dry wasteland – so many chamomiles – big as daises too – look, a bouquet next to me – in a big tin can – next to the bed – it smells of healing and goodness – how beautifully this little white of humility smells.

In Trikeri island, the women ‘assigned rotating tasks’ to make their exile on the island liveable: using asphodels they stuffed ‘mattresses and pillows’ and made ‘hats, mats and baskets’; using olive tree barks they ‘carved spoons and dishes’ and made decorative ‘wall hangings’; from pine trees, they took ‘branches and cones’ to kindle small hearths; ‘risking disciplinary measures’ the women would collect ‘little blue flowers’, stick them in ‘artful arrangements’ and send them as gifts to their ‘loved ones’.[11] Building upon and extending the notion of ‘flower power’,[12] we can say that in this case plant power for the displaced acted not only as a form and tool of peaceful resistance, but also as a tool for collective emplacement and survival,[13] resilience, adaptation and dignity.[14]

In a crucial testimony that pinpoints how the exiled appropriated as means of opposition the same non-human natures (stones, thorny bushes) that were used for their oppression, a group of women reworked and resisted the conditions of displacement on Makronisos. Summoned by the guards to uproot thorny bushes (afanes) with their bare hands:[15]

How could we uproot these thorny bushes without using some type of tool? … That’s when we heard old Koliousena calling us … ‘Come close girls, come close and look at me’ … And she started stepping on the afana from the root upwards, cutting the dry thorns near the root. Then she would use a stone to hit the afana near the root to cut it … We followed her lead and starting cutting afanes … hitting them with stones. Then, we started singing following the rhythm of the stone hits.

The testimony indicates that the exiles had forms of struggle in ‘alliance’ with nature that could spoil the plans of the guards and their own ‘alliance’ with nature. These forms of struggle are a form of reworking,[16] which is militant, collective, produces tangible results and challenges the conditions of displacement, although it may not struggle to change them per se. It could also be seen as a form of gendered solidarity in response to the oppression of the state and by extension, a moment of solidarity between urban and rural women – not always a given, due to cultural, educational and other differences. Finally, it is a rare case when ‘traditional knowledge’ about non-human nature, as symbolised here by Koliousena, is used collectively as a means of disrupting the designs of the state in conditions of carcerality.

Environmental history and plural ecologies of displacement

This Snapshot is linked to a minor strand of writing that pluralises the environment-displacement nexus. There a contour line that links this disparate scholarship via interlinked notions of survival, resistance and resilience; emplacement; dignity and reconciliation. The citation list is not exhaustive, but illustrative. White underscores the importance of refugee more-than-economic relations with livestock in creating a sense of ‘emplacement’ in camps run by the British in Ottoman Mesopotamia in 1918.[17] Hardy finds that birds in the Soviet Gulags helped inmates negotiate the harsh conditions of the unfamiliar world and provided ‘continuity’ with their previous lives.[18] In his landmark article, Colefinds in the voices of Jews fleeing in the Polish woods that the woods were both challenges and mediums of survival that transformed their identities and understanding of the world.[19] For Ferdinand, the Maroons exemplify how displaced communities can find liberation through nurturing relationships with their surroundings, underscoring the potential of ‘Black ecologies’ to foster forms of emancipation and community resilience.[20] Sundberg highlights how natural elements like deserts, rivers or cats inflect, disrupt and obstruct the daily practices of boundary enforcement.[21]

The provocation can be framed as: while climate change has to be mitigated, it also has to be adapted to, reworked, reconciled with and resisted. Environmental history can examine how displaced populations created meaningful connections in unfamiliar environments and frame emplacement not just as a survival strategy for the displaced, but as an approach to foster environmental connectedness in an era of ecological unpredictability. Examples where displaced persons maintained their dignity through nurturing relationships with their environment can serve as models for resilience in the face of the unequal impacts of climate change. By discussing how historically displaced communities used the natural environment as a tool of resistance, survival and reworking against oppressive conditions and extending these lessons to broader environmental strategies, environmental history could highlight collective agency in transforming and changing the structures and condition that lead to climate change-induced inequality.

Coda

Franco Fortini wrote in his rendition of the International: ‘those who have comrades will not die’ (chi ha compagni non morirà). If we can narrate and nurture comradely relationships with non-human nature, like the displaced of the Civil War era in Greece, perhaps we will not die either. Narrating these stories well requires an understanding that displacement was not an event, but an unequal geographical and historical process. During this process, ‘people lived, had hopes, tried to make sense of what was happening, and resisted’.[22] Environmental historians should (re)narrate the oppositional ecologies of displacement enacted by subaltern people: more-than-human ecologies of ‘survival, resistance, creativity, and the struggle against death’.[23]

[1] G. Farbotko, I. Boas, R. Dahm, T. Kitara, T. Lusama and T. Tanielu, ‘Reclaiming open climate adaptation futures’, Nature Climate Change 13(8) (2023): 750–51.

[2] https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGII_SummaryVolume.pdf

[3] D. Pharsakidis, Makronēsos (Athina: Skytalē, 1964).

[4] D. Mantzios, ‘Ē rētorikē tou engleismou stēn poiē tēs exorias’, Elliniko Vlemma 4 (2018): n.p.

[5] Α. Mavrooede, ‘Makronisos journal’, Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 5 (3) [1950 (1978): 115–28.

[6] B. Vardinogiannis and P. Arōnis, Oi misoi sta sidera (Athina: Filistōr, 1996).

[7] J. Dean, Comrade: An Essay on Political Belonging (London: Verso Books, 2019).

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5RZDDHjWCkI

[9] https://www.rizospastis.gr/page.do?publDate=25%2F7%2F04&pageNo=8&id=4762

[10] G. Ritsos, Trochies se diastaurōsi (Athina: Agra, 2008).

[11] V. Theodorou, ‘The Trikeri journal’, in E. Fortouni (ed.), Greek Women in Resistance (New Haven: Thelpini Press, 1986), pp. 120–36.

[12] K. Brickell, ‘Intervention: Flower Power—Khmer women’s protests against displacement in Cambodia and the United States’, in P. Adey, J.C. Bowstead, K Brickell et al. (eds), The Handbook of Displacement (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), pp. 541–47.

[13] A. Roy, ‘Dis/possessive collectivism: Property and personhood at city’s end’, Geoforum 80 (2017): A1–A11.

[14] B. Stoetzer, ‘Ruderal ecologies: Rethinking nature, migration, and the urban landscape in Berlin’, Cultural Anthropology 33 (2) (2018): 295–323.

[15] Μ. Mastroleōn-Zerva, Exorstes (Athina: Synchronē Epochi, 1986).

[16] C. Katz, Growing up Global: Economic Restructuring and Children’s Everyday Lives (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2004).

[17] B.T. White, ‘Humans and animals in a refugee camp: Baquba, Iraq, 1918–20’, Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (2) (2019): 216–36.

[18] J.S. Hardy, ‘Of pelicans and prisoners: avian–human interactions in the Soviet Gulag’, Canadian Slavonic Papers 60 (3-4) (2018): 375-406.

[19] T. Cole, ‘“Nature was helping us”: Forests, trees, and environmental histories of the Holocaust’, Environmental History 19 (4) (2014): 665–86.

[20] M. Ferdinand, ‘Behind the colonial silence of wilderness: “In marronage lies the search of a world”’, Environmental Humanities 14 (1) (2022): 182–201.

[21] J. Sundberg, ‘Diabolic Caminos in the desert and cat fights on the Rio’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101 (2) (2011): 318–36.

[22] M. Gessen, ‘Comparison is the way we know the world’, Die Zeit, 18 Dec. 2023. https://www.zeit.de/kultur/2023-12/masha-gessen-rede-hannah-arendt-preis-english (accessed 1 Aug. 2024).

[23] K. McKittrick, ‘Plantation futures’, Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17 (3 (42)) (2019): 1–15.

great! 104‘THE LIGHT OF DAY WAS OUR COMRADE’: ECOLOGIES OF FORCED DISPLACEMENT AND THE CHALLENGE OF UNFAMILIAR ENVIRONMENTS

LikeLike