In this blog, first published as Snapshot in Environment and History (May 2025), Kelly Hemmings explores how agricultural ‘improvement’ and agrochemicals have shaped and reshaped conceptualisations of arable plants (crops, wildflowers, weeds) in British fields since the 1750s.

Introduction

Arable plants, such as Cornflower (Centaurea cyanus), are the wild species that grow on cultivated land, having evolved alongside traditional low-intensity cropping practices.[1] In Great Britain, approximately 150 species have been classified as arable plants, of which 54 have been recorded as threatened with extinction and at least seven as regionally extinct (i.e. extinct in GB) or extinct in the wild.[2]

Commonly considered to be arable weeds, they have long been controlled within agroecosystems. The weed control methods used during the first agricultural revolution (c. 1750 – 1850)[3] were unlikely to have seriously reduced arable plant communities, but agricultural improvements of the mid-late nineteenth century began to do so.[4] Later, during the mid-late twentieth century, arable plant populations steeply declined in Europe, a trend that has been widely attributed to the simultaneous intensification of agriculture.[5] This depletion of arable plants has been associated with increased herbicide use and highly competitive crops (due to use of fertilisers, denser sowing and crop breeding), as well as several other changes in cultivation practices that were misaligned with arable plant adaptations [6]

Opportunities to study arable plants on land that has never been intensified are scarce in Western Europe.[7] Therefore, archival botanical and agricultural publications may provide extremely valuable alternative data sources.[8] This paper examines their potential to enhance present day understanding of these important plants by addressing these questions:

- Has the suite of species comprising the arable flora altered between the first agricultural revolution and the present?

- Can sentiment analysis (a method of numerically analysing the positive and negative tones of text) elucidate any alignment between historic and present day perception and conservation status of arable plants?

- To what extent was the ecological value of arable plants historically recognised?

Methods

The first agricultural revolution was selected as the comparative time period because the era pre-dated widespread declines in arable plant populations.[9] Additionally, Linnean binomial nomenclature was in common usage by this time, enabling accurate taxonomic verification. Botanical nomenclature followed World Flora Online.[10]

To establish the composition of arable flora during the first agricultural revolution, we listed species associated with ‘arable’,[11] ‘cultivated’,[12] ‘cornfield’, ‘corn’,[13] ‘crop’ or ‘fallow’[14] land-uses through manual reading of seven archival botanical and agricultural publications.[15] We subsequently compiled a comparative list of arable plant species from three present day ecological and agricultural publications: species were classified as ‘wildflower’ if listed by Wilson and King and/or Plantlife;[16] as ‘weed’ if only listed by the Agricultural and Horticultural Development Board;[17] or as ‘wildflower and weed’ if listed in either of the former plus the latter. To explore recognition of the ecological value of arable plants in the archival publications, we tallied species’ interactions according to taxon group.

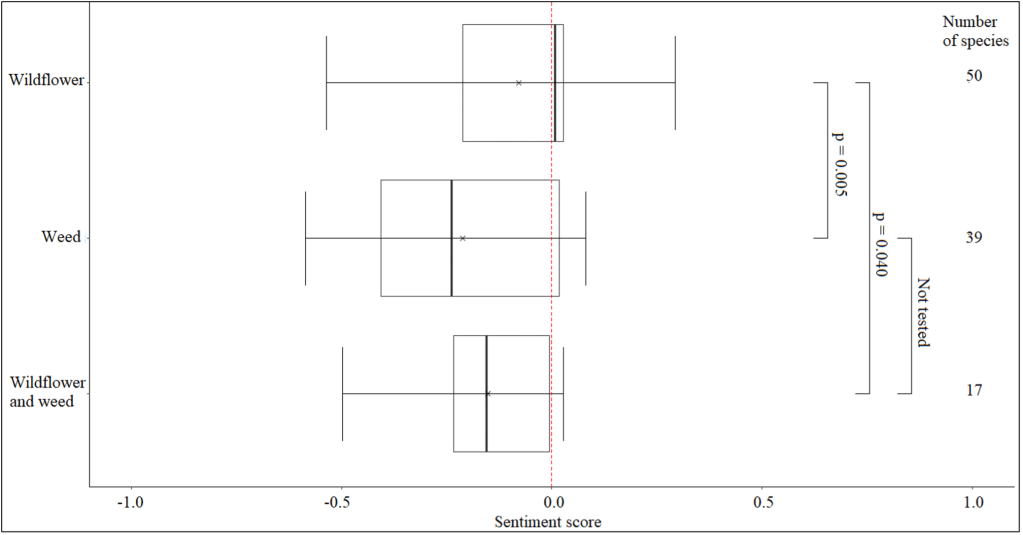

Sentiment analysis was used to quantify historic perceptions of arable plants. From the multiple archival publications, we transcribed species-specific text excerpts that related to: harm to farming; ‘weed’, ‘wildflower’ or ‘noxious’ categories; abundance; aesthetics; control (e.g. Figures 1 and 2). We carried this out for species that: (a) had been taxonomically described before 1840 and were associated with arable land in at least one of the seven archival publications; and (b) were listed as arable plants in at least one of the present day publications and had an available Red List conservation status.[18]We then merged these texts into a single paragraph for each species using R script and code libraries, which were processed using Google Cloud Natural Language API’s sentiment analysis function via R scripts and libraries to score each species on a scale of -1.000 to 1.000.[19] We used Mann-Whitney U to test for difference between the sentiment scores of arable plants currently perceived to be ‘wildflowers’ (n = 50) versus ‘weeds’ (n = 39), and ‘wildflowers’ versus ‘wildflowers and weeds’ (n = 17). For these comparisons, variances were equal (p > 0.05 Levene’s test) but as this was not the case for the third possible pairing, it was not tested. Ethical approval: 20235521-Hemmings

Results and Discussion

Composition of arable flora

In total, 164 plant species were associated with arable land in the archival publications and 206 in the present day publications, of which 118 were in common.[20] The shared species comprised a cross-section of arable specialists e.g. Sharp-leaved Fluellen (Kickxia elatine); generalists e.g. Scarlet Pimpernel (Lysimachia arvensis); and intermediate arable-adapted species e.g. Common Fumitory (Fumaria officinalis).[21]

The discrepancy between historic and current arable flora composition was explained in several ways. The date of first taxonomic description was necessarily a factor, as was the interval between this and inclusion in one of the archival general interest publications. Of the 206 present-day arable plant species, 174 had been taxonomically described before publication of the earliest archival publication in 1777 and a further three had been described and published between this time and the latest archival publication in 1840. Only twelve present-day arable plant species, although taxonomically described before 1777, were not included in any of the archival publications, and one was published but lacked its text.

Of the 177 described and published species, 46 were not arable-associated in the archival publications. These were mainly generalists such as Annual Meadow-grass (Poa annua).[22] However, the non-arable associations of Ground Pine (Ajuga chamaepitys) and Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) were surprising as both are classified as threatened arable plants,[23] and Ground Pine is protected under Schedule 8 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981). Conversely, a further 46 species were arable-associated in archival but not modern publications.[24]

Past and present perceptions

Weed perception text was available for 106 species.[25] Sentiment analysis revealed scores ranging from the most negative (-0.683) for Stinking Chamomile (Anthemis cotula):

‘Abounds to that degree in some cornfields, as to greatly diminish the crop.’[26]

‘This disagreeable weed.’[27]

‘Blisters the hands of those who gather it.’[28]

‘Rampant weeds which encumber the soil.’[29]

‘Noxious and wildflower.’[30]

to the most positive (0.417) for Field Woundwort (Stachys arvensis):

‘As a weed it gives little trouble.’[31]

‘Wildflower.’[32].

Results indicate that socio-ecological perceptions of arable plants largely held true between the first agricultural revolution and the present. The median sentiment score for species currently categorised as ‘wildflowers’ (0.008) was statistically significantly more positive than for species categorised as ‘weeds’ (-0.239) (p = 0.005) and as ‘weed and wildflower’ (-0.155) (p = 0.040) (Figure 3). Cornflower was one of few species to include explicitly positive language (among otherwise negative sentiment): ‘Enlivens fields by the brilliancy of its colour’.[33] Notably, this species has long been identified as aesthetically and culturally important.[34]

The qualitative archival information often explained current conservation status. The archival descriptions of Lamb’s Succory (Arnoseris minima) (regionally extinct), Field Cow-wheat (Melampyrum arvense) (endangered) and Thorow-wax (Bupleurum rotundifolium) (critically endangered) all use the words ‘not common’,[35] ‘rare’[36] or ‘rarer’[37]respectively.[38] Conversely, for Corncockle (Agrostemma githago) (once registered as extinct in the wild) (‘A great pest to the farmer … Too common’),[39] its former profusion has resulted in seeming eradication as an archaeophyte. [40]

Good weeds?

Pitt’s chapter on ‘Weeds and weeding’ differentiated the most pernicious weeds from those of less concern (Figure 2).[41]This reasoning was a precursor to modern management, whereby pernicious weeds are controlled, while arable specialists with low competitive ability and high biodiversity value are the focus of conservation.[42] One or more ecological interactions were described in an archival publication for 21 of the 118 arable plant species common to past and present. Thirteen were associated with butterfly or moth species, nine with birds, three with fungi, one with a beetle and one with bees.

Conclusion

In summary, this study conducted a novel comparison of the composition and perceptions of arable flora between the first agricultural revolution and the present. The archival sources revealed that the arable associations of a quarter of arable plant species were previously considered stronger or weaker than in the present, which had implications for conservation management and prioritisation. We also found historical descriptions of rarity, which partly explained current conservation status. Historical and present sources aligned in their perception of arable plants as weeds versus wildflowers: such legacy reputations may have further contributed to the decline of some species. The archival sources began to recognise the ecosystem services of species otherwise considered as weeds, which anticipated current ecological reasoning. Overall, the quantitative and qualitative analyses uncovered rich and valuable evidence held within archival agricultural and botanical publications, that, given the rarity of centuries-long field experiments, are worthy of consultation prior to arable plant conservation projects.

[1] A.J. Byfield and P.J. Wilson, Important Arable Plant Areas: Identifying Priority Sites for Arable Plant Conservation in the United Kingdom(Salisbury: Plantlife, 2008), p. 5.

[2] Ibid. p. 6.

[3] M. Overton, ‘Re-establishing the English agricultural revolution’, The Agricultural History Review 44 (1) (1996): 1–20.

[4] P. Wilson and M. King, Arable Plants: A Field Guide (Old Basing, Hampshire: Wild Guides, 2003), p. 30.

[5] H. Albrecht, J. Cambecèdes, M. Lang and M. Wagner, ‘Management options for the conservation of rare arable plants in Europe’, Botany Letters 163 (4) (2016): 389–415.

[6] Ibid.

[7] S.R. Moss, J. Storkey, J.W. Cussans, S.A. Perryman and M.V. Hewitt, ‘The Broadbalk long-term experiment at Rothamsted: what has it told us about weeds?’ Weed Science 52 (5) (2004): 864–73.

[8] D. McCollin, L. Moore and T. Sparks, ‘The flora of a cultural landscape: environmental determinants of change revealed using archival sources’, Biological Conservation 92 (2) (2000): 249–63; C.D. Preston, ‘Perceptions of change in English county Floras: 1660–1960’, Watsonia23 (3): 287–304.

[9] Wilson and King, Arable Plants, p. 30.

[10] WFO, World Flora Online. Worldfloraonline.org (accessed 29 June 2024); Supplementary Material Parts A and B: https://rau.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/16863/

[11] Land used for growing crops.

[12] Land that is prepared for growing crops e.g. by ploughing.

[13] In the traditional UK sense, corn usually means wheat or similar cereal crop (rather than maize in the US sense).

[14] Arable land that has been left to ‘rest’ without sowing..

[15] W. Curtis, W. Darton, S. Edwards, W. Kilburn, F. Sansom, J. Sowerby and B. White, Flora Londinensis. Vol. 5. (London: Printed for and sold by the author, 1777). Smithsonian Libraries and Archives: https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.62570 (accessed 31 Oct. 2024); W. Curtis, A Catalogue of the British Medicinal, Culinary, and Agricultural Plants Cultivated in the London Botanic Garden by William Curtis, (London: Royal College of Surgeons, 1783): https://wellcomecollection.org/works/wcmqc3ft (accessed 18 Oct. 2023); J.E. Smith and J. Sowerby, English Botany (London, J. Davis, 1790–1814): https://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/idurl/1/11302 (accessed 18 Oct. 2024); W. Pitt, A General View of the Agriculture of Leicestershire. (Wolverhampton: The Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement, 1809); B. Holdich, ‘An essay on the weeds of agriculture’, in G. Sinclair (ed.), Posthumous Works of Benjamin Holdich, 2nd ed. (London: J. Moyes, 1826): https://archive.org/details/anessayonweedsa00sincgoog/page/n4/mode/2up (accessed 13 Oct. 2024); W.J. Hooker, The British Flora (London: Longman, Orme, Brow, Green, and Longman, 1838): https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.50407 (accessed 26 Oct. 2024); H. Baines, The Flora of Yorkshire (London: Longman, Orme, Brow, Green, and Longman, 1840): https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.138592 (accessed 18 Oct. 2023); Supplementary material Parts A and B: https://rau.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/16863/

[16] Wilson and King, Arable Plants; Plantlife, Important Arable Plant List and Scores (Salisbury: Plantlife, 2015).

[17] Agricultural and Horticultural Development Board, The Encyclopedia of Arable Weeds (Kenilworth: AHDB, 2018).

[18] Supplementary material Part A: https://rau.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/16863/

[19] Google Cloud, Natural Language API (2024): https://cloud.google.com/natural-language/ (accessed 12 Dec. 2023); R Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (2022): https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 12 Dec. 2023); H. Wickham, tidyverse(2023): https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyverse (accessed 12 Dec. 2023); M. Edmondson, googleLanguageR: Call Google’s ‘Natural Language’ API (2020): http://code.markedmondson.me/googleLanguageR/https://github.com/ropensci/googleLanguageR,https://docs.ropensci.org/googleLanguageR/ (accessed 12 Dec. 2023); P. Schauberger and A. Walker A. openxlsx: Read, Write and Edit xlsx Files (2023): https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=openxlsx (accessed 12 Dec. 2023); Supplementary Material Part C: https://rau.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/16863/

[20] Supplementary material Part A: https://rau.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/16863/

[21] G. Fried, S. Petit, and X. Reboud, ‘A specialist-generalist classification of the arable flora and its response to changes in agricultral practices’, BMC Ecology 10 (20) (2010): 1–11.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Plantlife, Threatened Arable Plants: Identification Guide (Salisbury: Plantlife International), p. 2.

[24] Supplementary material Part B: https://rau.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/16863/

[25] Supplementary material Part A: https://rau.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/16863/

[26] Curtis, A Catalogue. p. 73, 102

[27] Smith and Sowerby, English Botany, Pl. 1772.

[28] Hooker, The British Flora, p. 288.

[29] Holdich, An Essay, p. 47.

[30] Curtis, Flora Londinensis, Pl. 61.

[31] Smith and Sowerby, English Botany, Pl. 1154.

[32] Curtis, A Catalogue, p. 121.

[33] Curtis, Flora Londinensis, Pl. 62.

[34] G. Pinke, V. Kapcsándi and B. Czúcz, ‘Iconic arable weeds: The significance of corn poppy (Papaver rhoeas), cornflower (Centaurea cyanus), and field larkspur (Delphinium consolida) in Hungarian ethnobotanical and cultural heritage’, Plants 12 (1) (2023): 12010084.

[35] Smith and Sowerby, English Botany, Pl.9 5.

[36] Ibid. Pl. 53.

[37] Baines, Flora of Yorkshire, p. 144.

[38] Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Conservation Designations for UK taxa: https://hub.jncc.gov.uk/assets/478f7160-967b-4366-acdf-8941fd33850b (accessed 19 Oct. 2023).

[39] Smith and Sowerby, English Botany, Pl. 741.

[40] C.M. Cheffings, L. Farrell, T.D. Dines, R.A. Jones, S.J. Leach, D.R. McKean, D.A. Pearman, C.D. Preston, F.J. Rumsey and I. Taylor. ‘The vascular plant red data list for Great Britain. Species status, Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough: England 7 (2005), 1–116.

[41] Holdich, An Essay.

[42] J. Storkey and D. Westbury, ‘Managing arable weeds for biodiversity’, Pest Management Science 63 (2007): 517–23.