In this blog to accompany her just-published article ‘The Contested History of the Ecological Indian Trope: Politics of Knowledge in Conservation Science and Anthropology 1990–2000’ in Environment and History Rithma Kreie Engelbreth Larsen interrogates the history of the ‘Ecological Indian’ trope and the surrounding debate, which highlights the broader question of the legitimacy of Indigenous knowledge and the pivotal role of historical narratives in questions of agency and legitimate authority.

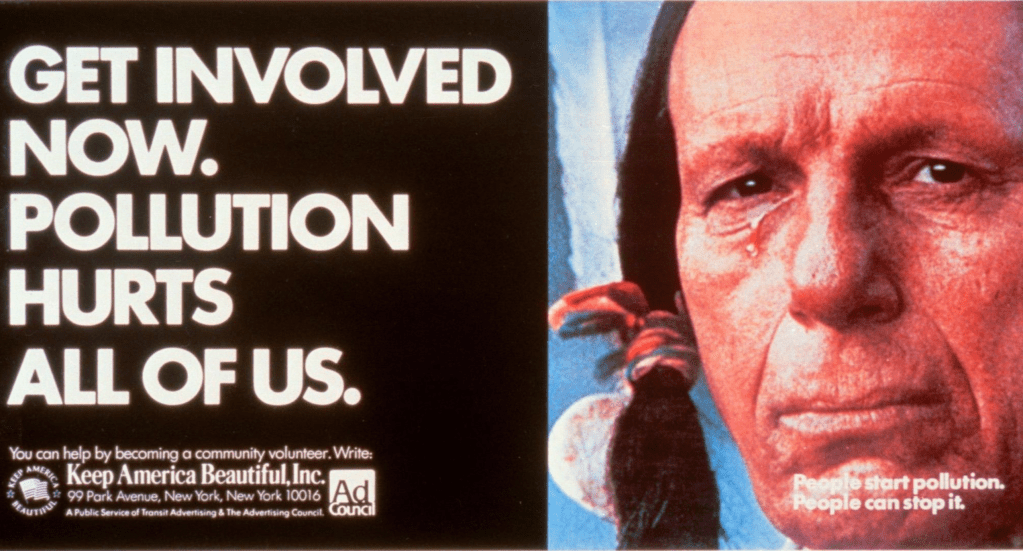

In April 2023, UN Secretary-General António Guterres declared: ‘Indigenous Peoples hold many of the solutions to the climate crisis and are guardians of the world’s biodiversity … It is a way of life – stretching back millennia. We have so much to learn from their wisdom, knowledge, leadership, experience, and example.’[1] This statement epitomises the growing view of Indigenous peoples as natural conservationists bearing deep environmental insights.[2] But, to some scholars, the statement also epitomises what they deem an undying and problematic commitment to what has been coined the Ecological Indian trope, a more recent version of the classic trope of the Noble Savage.[3]

The broader concept of ‘The Noble Savage trope’ refers to the oft-repeated idea that Western thought harbours a long-standing and problematic trope that idealises Indigenous and non-Western peoples as living in a pure, uncorrupted state of nature, supposedly untouched by the vices of civilisation. Yet the presumed historical ubiquity of this trope is more contested than often acknowledged – ironically, a misconception that forms part of the very mythology surrounding it. The criticism of the ‘noble savage’ myth is a formative constituent of the anthropological discipline, continuously upholding the idea that ‘belief’ in the Noble Savage is widespread and constantly threatens scholarly nuance and critical thinking.[4] While this trope certainly exists in scholarly discourse, the present article argues that it mostly exists as a rhetorical weapon that targets a particular view of Indigenous peoples that attributes to them what is perceived as an exaggerated ecological insight and practice.

This article examines a particular amalgamation of this long-standing debate in more recent historical times, focusing on the 1990s. In 1995, anthropologist Shepard Krech III published the book The Ecological Indian, in which he argued that the Noble Indian[5] stereotype primarily ‘is a foil for critiques of European or American society’ – and, secondly, that it also became ‘a self-image’ for Indigenous people around the world.[6] Krech’s work did not go unchallenged but spurred a broader debate on the Ecological Indian trope’s origin, its perceived pervasiveness and its general status as a trope or historical fact[7] – pervaded by efforts to debunk what many saw as a romanticised and problematic construct.

This article revisits that debate as a pivotal moment in the conceptual genealogy of Indigenous knowledge. Rather than solely examining the truth or falsehood of the trope, the 1990s scholarly contentions highlight the broader question of the legitimacy of Indigenous knowledge. Revisiting this debate allows us to better understand how historical narrative and political authority intersect in shaping ideas about Indigenous-environmental relationships.

The political stakes underlying the scholarly debate over Indigenous sustainability are explored through an examination of the contested meanings of the ‘Ecological Indian’ trope in the 1990s and early 2000s, particularly in North America. At the heart of this debate lies a struggle over narrative authority, one that plays out along two axes: Which account best reflects the historical record? And which is more politically effective in advancing Indigenous rights and recognition? This article argues that these two dimensions, the historical and the political – often treated as distinct – are in fact deeply entangled. Decisions about what counts as credible historical evidence, and how terms like ‘conservation’ are defined, have far-reaching consequences for the status and legitimacy of Indigenous knowledges.[8] In this context, environmental historians greatly influence which forms of environmental practice and knowledge are validated.

Bearing in mind these two dimensions, this article traces the emergence and consolidation of two dominant cluster positions through a close reading of key texts of the period. These stances reflect two cluster positions: one that emphasises the trope’s constructed, performative dimensions, and another that insists on the enduring truth of Indigenous peoples’ sustainable relationships with the natural word. The constructivist position contends that the Ecological Indian is a recent, essentialising invention that risks reinforcing stereotypes and undermining Indigenous political struggles. The transhistorical position, by contrast, holds that rejecting the continuity of Indigenous ecological knowledge is false and constitutes an epistemic injustice – erasing deeply-rooted systems of land stewardship.

Proponents of the ‘transhistorical’ position often invoke romanticised depictions of Indigenous communities, characterising them as ‘guardians of the forest,’ ‘tribal elders,’ ‘natural conservationists,’ or ‘sustainable resource managers.’[9] Such portrayals are frequently critiqued as iterations of the Noble Savage trope, including its contemporary manifestations, the Ecologically Noble Savage and the Ecological Indian. In contrast, those adopting a ‘constructivist’ stance shaped by critiques of these tropes tend to rely on markedly different representations, casting Indigenous peoples as ‘primitive polluters,’[10] ‘environmental destructors,’[11] ‘identity performers,’[12] or ‘hunters-into-extinction.’[13]These counter-narratives reflect a broader skepticism among some scholars, who contend that notions of Indigenous conservation are not only idealised but contradicted by historical evidence that, in their view, instead points to patterns of unsustainable environmental practices.

By developing this distinction, I shed light on the broader stakes of historical narrative in processes of political inclusion. While historians may be inclined to dismiss the transhistorical view as romantic or ahistorical, failing to fully engage its significance risks reproducing epistemic injustices toward Indigenous communities.[14] Labelling a position as an instance of the trope often functions – intentionally or not – as a rhetorical weapon, one that delegitimises those affirming the value of Indigenous ecological knowledge. In many cases, critics targeted a strawman version of Indigenous advocacy that bore little resemblance to serious scholarship.

The study explores a complex discursive landscape: on one side, efforts to dismantle and debunk what critics saw as a romanticised trope; on the other, a commitment to amplifying Indigenous voices in environmental discourse. What stands out in the academic discourse on the Ecological Indian trope is that both sides justify their positions by invoking the potential political consequences of the opposing stance. Proponents of Indigenous environmental continuity argue that denying historical realities undermines present-day right claims, while critics warn that maintaining an idealised image makes those same claims vulnerable when inconsistencies arise.

By examining the scholarly debate over Indigenous sustainability, this article highlights the political stakes embedded in the environmental histories we construct. The debate surrounding the ‘Ecological Indian’ trope – particularly as it played out in scientific and academic forums during the 1990s – was marked by a notable absence of Indigenous voices. This exclusion reflects longstanding patterns of epistemic marginalisation and raises critical questions about who gets to produce environmental knowledge. The relative absence of Indigenous perspectives in the scholarship should not be mistaken for a complete lack of influence; rather, it underscores the structural and epistemological exclusions that shaped academic discourse, even as Indigenous voices continued to inform and challenge environmental debates from the margins.

This article makes two main contributions to environmental history. First, it revisits a largely overlooked but influential 1990s debate over the ‘Ecological Indian’, which helped shape how Indigenous ecological knowledge has been framed and contested. Though often treated as marginal, the debate raises fundamental questions about historical narrative, representation, and authority. Second, the article offers a conceptual framework that moves beyond the binary of debunking or defending romanticised views of Indigenous sustainability. It identifies two central points of contention – historical accuracy and political efficacy – giving rise to two main clusters: a constructivist view that sees the trope as a modern essentialist invention and a transhistorical view that affirms the continuity of Indigenous ecological knowledge. Rather than a question of correcting myths, the debate reveals deeper struggles over how Indigenous knowledge is legitimised – struggles that continue to shape environmental humanities discourse today, especially around nature, wilderness and ecological preservation.

While many environmental humanities scholars continue to challenge the idea that Indigenous knowledge offers pathways to sustainability and accuse this notion of being romanticising and essentialising, a range of Indigenous thinkers emphasise the urgency of preserving these ‘ancient teachings’.[15] Scholars such as Robin Wall Kimmerer, Kyle Powys Whyte and Linda Tuhiwai Smith argue that Indigenous ecological knowledge has a long history and offers crucial guidance for confronting today’s environmental crises. In this light, the constructivist stance risks overlooking the political stakes of dismissing Indigenous ecological knowledge as merely performative – and how the dismantling of the Ecological Indian trope has broader implications than might be intended.

Historical narratives play pivotal roles in questions of agency and legitimate authority. As argued throughout this article, there is no separating history from politics and so we must – as many of the scholars on both ‘sides’ do – continuously ask of the historical narratives and frameworks we employ: who stand to gain, and who stand to lose? This article argues that the effort devoted to dismantling the Ecological Indian trope may be, in many respects, misdirected. Too often, such critiques either engage with a strawman or risk casting doubt on the legitimacy of Indigenous knowledge itself – an outcome that is neither constructive nor desirable if we are to foster meaningful collaboration with Indigenous knowledge holders, especially amid the escalating ecological crises confronting the planet.

The concept of Indigenous knowledge indicates a recent shift in environmental history, as it enables Indigenous peoples to demand space and exercise a voice in global politics. As historians, we cannot pretend that our accounts do not play a key role in these negotiations of political agency, especially as we are increasingly facing calls to determine the history of human-environmental interaction and calls to identify its heroes and its villains. The oft-repeated answer of ‘neither’ really provides very little satisfaction at this point.

[1] António Guterres, ‘“Let Us Learn from Indigenous Peoples” to Create Peace, Sustainability, Prosperity, Secretary-General Says at Opening of Permanent Forum’, United Nations: https://press.un.org/en/2023/sgsm21767.doc.htm (accessed 6 June 2024)

[2] In recent decades, ‘the Indigenous knowledge holder’ has developed a strong presence in a range of contexts, particularly in science-policy institutions. See e.g. Arun Agrawal, ‘Dismantling the divide Between Indigenous and Western knowledge’, Development and Change 26 (3) (1995): 413–39; Fikret Berkes, Sacred Ecology (New York: Routledge, 1999/2008); Sheila Jasanoff and Marybeth Long Martello (eds), Earthly Politics. Local and Global in Environmental Governance (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004); Candis Callison, How Climate Change Comes to Matter: The Communal Life of Facts (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014); Kyle Whyte, ‘Indigenous climate change studies. Indigenizing futures, decolonizing the Anthropocene’, English Language Notes 55 (2017): 153–62; Douglas Nakashima, Jennifer T. Rubis and Igor Krupnik, ‘Indigenous Knowledge for climate change assessment and adaptation: Introduction’, in Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation. Local and Indigenous Knowledge 2, ed. by Douglas Nakashima, Jennifer T. Rubis and Igor Krupnik (Cambridge and Paris: Cambridge University Press and UNESCO, 2018), pp. 1–20; Eduardo S. Brondízio et al., ‘Locally based, regionally manifested, and globally relevant: Indigenous and local knowledge, values, and practices for Nature’, Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46 (2021): 481–509.

[3] Shepard Krech III, The Ecological Indian. Myth and History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999). For more on the history of the trope and its roots in the Noble Savage trope, see Ter Ellingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage (London: University of California Press, 2001).

[4] Ter Ellingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage (London: University of California Press, 2001).

[5] ‘Noble Indian’, ‘Noble Savage’ and ‘Noble Ecological Savage/Indian’ are treated as variations of the same general trope most often referred to as the Ecological Indian. This is not entirely accurate in a longer historical perspective, but I treat them as synonyms throughout the article, as do the scholars whose work I examine (unless stated otherwise).

[6] Krech, The Ecological Indian, pp. 214, 26.

[7] See e.g. Vine Deloria Jr, ‘The Speculations of Krech: A review article of Krech, Shepard The Ecological Indian W.W. Norton and Company. New York and London 1999’, Worldviews: Global Religion, Culture, and Ecology 4 (2000): 283–93; Dan Flores, ‘The Ecological Indian: Myth and history’, The Journal of American History 88 (2001): 177–78.

[8] In alignment with various Indigenous scholars, I occasionally pluralise Indigenous knowledges to indicate its heterogenous character.

[9] E.g., Kent Redford, “The Ecologically Noble Savage,” Cultural Survival Quarterly 9 (January 1991): 46; Krech, The Ecological Indian.

[10] Terry Rambo, Primitive Polluters: Semang Impact on the Malaysian Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystem (Ann Arbor: Regents of the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, 1985).

[11] Jared Diamond, “Archaeology: The Environmentalist Myth,” Nature 326 (November 1986): 19-20; Robert B. Edgerton, Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony (New York: Free Press, 1992).

[12] E.g. Beth Conklin, “Body Paint, Feathers, and VCRs: Aesthetics and Authenticity in Amazonian Activism,” American Ethnologist 24 (November 1997): 711-734; John L. Comaroff & Jean Comaroff, Ethnicity, Inc. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009).

[13] Krech, The Ecological Indian.

[14] E.g. Rebecca Tsosie, ‘Indigenous peoples, anthropology, and the legacy of epistemic injustice’, in Ian James Kidd, José Medina and Gaile Pohlhaus, Jr (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice (London: Routledge, 2017), pp. 356–69.

[15] Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, p. 259.