This blog, exploring ‘how the plastic bag became an iconic symbol of environmental degradation’, republishes a Snapshot by Nils Johansson, originally published in Environment and History (August 2025).

The plastic bag is a mundane consumer product. It consists of just one inexpensive material, intended to carry other, more important, items. It is one of those objects that becomes more visible when it is out of context. But the plastic bag easily ends up there, out of context, demanding our attention. This essay explores how the plastic bag became an iconic symbol of environmental degradation, with a special focus on Sweden, the very place where the bag was invented. By combining perspectives from marketing and new materialism, this essay deepens our understanding of how the plastic bag was institutionalised.

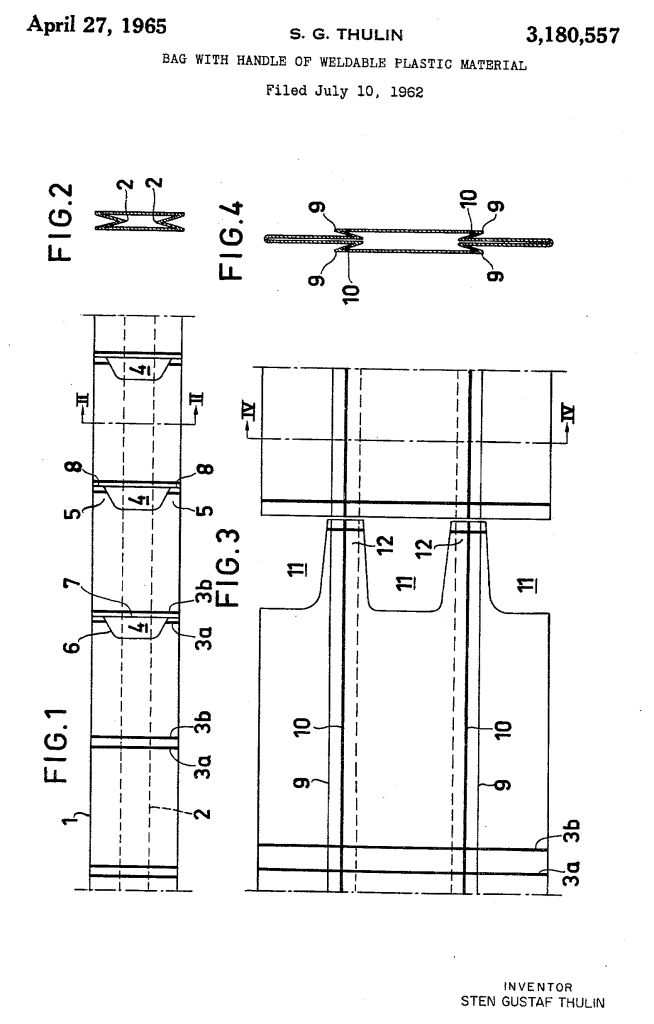

In the late 1950s, Curt Lindquist was in the basement of his house in southern Sweden, experimenting with a new and promising material: plastic. Lindquist was then the CEO of the company Celloplast, an innovation hub owned by the Swedish Cooperative Union. Just a few years earlier, he had famously borrowed his wife’s meat grinder to shred sponges into what became the modern dishcloth: the Wettex. This time, by cutting and heat-sealing pieces of plastics together, he created the first seamless plastic bag; the Teno-bag.[1] Unlike earlier designs, the handles were not attached in a separate process. The patent application, Figure 1, was filed by Celloplast’s sales manager, Sten Thulin, and granted in 1965.[2]

The plastic bag was lightweight, yet capable of carrying hundreds of times its weight, and was resistant to moisture. Nonetheless, it met with some concerns. Earlier versions of plastic bags from the 1950s tended to cling to the skin. Following repeated suffocation accidents involving children, a Swedish newspaper described the plastic bag in 1965 as a ‘suffocation device’.[3] Subsequently, the national authorities warned against leaving children alone with plastic bags.

To convince consumers that the Teno-bag was something entirely different, it was semantically distinguished from the plastic bag. The new Teno-bag was not a plast-påse [Swedish for plastic bag], but a bär-kasse. The term kasse has no direct English translation, but suggests a medium-sized container, between the size of an English ‘bag’ and ‘sack’. To eliminate any ambiguity, the word bär (carry) was added in front to clarify that the bag was designed to be carried and nothing else. Thus, a bärkasse became synonymous with a bag always equipped with handles: a carrier bag.

Additionally, Celloplast promoted the plastic bag as a solution for household waste management, by replacing the traditional slop bucket, just tie the ‘ears’ of the bag together.[4] However, convincing retailers proved more challenging, since single-use bags represented a cost for them. These bags were initially provided free of charge, as retailers believed it was ‘hardly realistic … that consumers would pay to carry around advertisements’.[5]

The major breakthrough came in 1967 when Systembolaget, Sweden’s state alcohol monopoly, adopted the Teno-bag. Previously, Systembolaget staff wrapped each bottle in paper to anonymise branding and reduce the appeal of carrying bottles home in open baskets. [6] One of Systembolaget’s mandates, then as now, was to discourage alcohol consumption. To avoid the wrapping producer and ‘save seconds’, Systembolaget tested two types of carrier bags in 1967: the plastic versus the paper bag.[7]

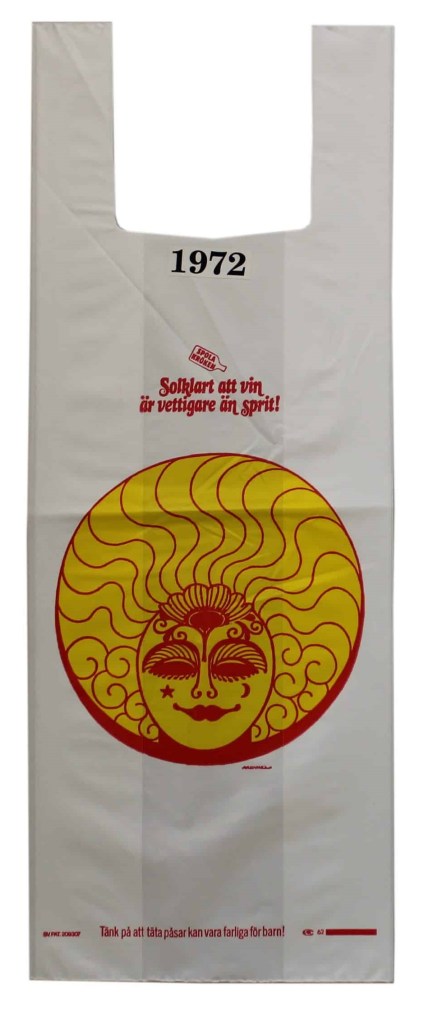

The test revealed that plastic bags took three seconds longer to pack than paper bags, due to their flimsiness, which made them difficult to open.[8] However, thanks to their versatility, the plastic bags were equally suitable for carrying home two wine bottles or six beer cans. The plastic bag offered also a higher advertising value. Compared to brown paper bags, the print on white plastic bags stood out in sharper contrast. By printing messages such as ‘Pour away the booze’, Figure 2, the plastic bag became a more effective medium for Systembolaget to communicate its mission of discouraging alcohol consumption.[9] Additionally, the durability of plastic compared to paper extended the bag’s advertising value, as it was often reused in different contexts, for example, to carry wet swimwear home.

A decisive factor for the plastic bag’s success was its lower cost compared to paper bags. This cost advantage stemmed from the design of the Teno-bag, which could be rolled continuously onto a compressed tube, saving both storage space and transportation costs. While single-use bags represented an expense for retailers, they encouraged spontaneous and larger purchases in stores. The conventional basket limited the number of products customers could carry home, thereby capping the volume of purchases. Single-use bags also facilitated unplanned visits to stores. Hence, the single-use bags became, according to the economist Johan Hagberg, a critical component of the emerging shopping culture.[10]

Within a few years in the late 1960s, the consumption of carrier bags in Sweden skyrocketed. In 1967, 400 million bags were purchased in the country. Five years later, that figure rose to a billion bags of which 600 million were plastic, primarily produced by Celloplast.[11] Initially, the bags were free. However, once customers grew accustomed to single-use bags to both carry goods home and for disposal purposes, retailers demanded payment. This shift turned single-use bags into a multi-million business, through charging significantly higher profit margins on bags than other goods.[12]

Thanks to its patent, Celloplast held a monopoly on the bag production and expanded internationally during the 1970s. Imported plastic bags became particularly popular, just a ferry ride away from Sweden, in the former Eastern Bloc. Here, the plastic bags, like chewing gum, served as symbols of modernity and connections to the idealised West. They were treated with care: washed and repaired. Visiting Western journalists often stereotyped Eastern citizens as a people defined by carrying shopping bags.[13] For those living in the planned economy, however, carrying bags offered preparedness if goods suddenly became available in stores.[14]

Celloplast faced its first major setback in 1977 when the oil company Exxon Mobil successfully invalidated Celloplast’s patent in a US court, which paved the way for global massproduction.[15] Gradually, Celloplast lost market share, and was sold by the Swedish Cooperative Union in the late 1980s. The Teno-bag, resembling a sleeveless tank top (Figure 1), became nevertheless the global standard model for most plastic bags; from colorful shopping bags to transparent produce bags. According to the UN, a trillion plastic bags are used globally each year, equivalent to 2 million per minute. [16]

The Teno-bag not only set the standard for design, but also evolved into a symbol of environmental degradation. Particularly powerful were images of marine debris. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, uncovered by Charles Moore in 1997, challenged the idyllic perception of the ocean as a pristine refuge for wildlife. As with previous environmental campaigns, images of affected animals struck a chord with the public. Chris Jordan’s haunting photographs from 2009 of albatross carcasses filled with plastic debris on Midway Atoll are hard to forget, as the corpses contained our discarded consumer products.[17]

Paradoxically, the plastic bag became a symbol of littering and environmental destruction just because of its successful materiality. While most of the marine plastic pollution consists of micro-plastics, it is the brightly colored plastic bags that catch our eye. The very qualities that make plastic bags advantageous in commerce – lightness, durability, water resistance and visibility – became their worst environmental enemies.

Due to enormous sales volumes, even a small fraction of lost plastic bags means massive quantities of litter. Once discarded, the bags rarely stay in one place. They drift rhythmically, carried by wind or water currents. Since Earth’s microorganisms cannot break down the long polymer chains of plastic, these materials can persist in the environment for centuries. Microorganisms find no foothold, no crevices to penetrate, and slide helplessly off. The plastic bag has an unearthly ontology. As the Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard observes, they ‘seem to exist in a place beyond everything else’, travelling vast distances and appearing in the most unexpected locations.[18]

The movement of plastic bags in the ocean mimics jellyfish, causing predators to consume them, retaining them in their stomachs for the rest of their lives. Reports of marine animals dying after ingesting plastic bags are numerous. For example, the first Cuvier’s beaked whale was discovered in Norway after it stranded with thirty plastic bags in its stomach.[19]

Although plastic bags posed a choking hazard to children from their introduction, it was the threat they posed to marine animals that finally spurred sufficient political will to curb their ‘stubborn materiality’.[20] By July 2018, according to the UN, 66 per cent of all countries had implemented restrictions on plastic bags, making it one of the most widespread environmental policies.[21] The Swedish government implemented a plastic bag tax of 3 kronor (€0.25) in May 2020.

The problem of littering plastic bags was, however, noted already at their introduction. In the city of Jönköping, where the Teno-bags were first tested, a consumer cooperative store refused in 1972 to continue selling them after their customers complained about finding plastic bags with the cooperative logo littering the ground.

The plastic bag appears to resist not only all forms of earthly microorganisms, but also political protests. When it became apparent that the plastic bags were produced by another company within the cooperative, they were quickly reinstated by the store. In a 1972 double-page advertisement in the magazine Vi, owned by the cooperative, the Swedish Plastics Federation declared: ‘Plastics are not harmful to the environment’ and ‘it’s not the plastic bag’s fault if it’s discarded in nature’.[22] Additionally, the Plastics Federation emphasised that increased consumption of bags was beneficial, as ‘greater volumes’ were needed before recycling could become profitable.

Both evolution and politics seem to lack tools to challenge the plastic bag. The delays in concluding the global agreement against plastic pollution demonstrate its resilience. Another example is the short-lived plastic bag tax, which unlike the enduring littering of plastic bags, had a brief lifespan when it was abolished in Sweden in November 2024. Sweden may be one of the first countries to roll back its plastic bag restrictions, but it is likely not the last, given the strong global lobbying efforts against the restrictions.

The debate between proponents and critics of the restrictions has been so intense in Sweden that the plastic bag itself got largely forgotten. Yet the plastic bag compels people to discuss politically sensitive issues, such as everyday consumption. Moreover, restricting the plastic bag is primarily justified by concern for nature and animals rather than for humans. Thus, the plastic bag offers a compelling lens through which to examine the complex interplay between consumption, ethics, nature, materiality and politics.

[1] B. Gavér, Norrköpings Tidningar, 22 July 2015.

[2] S.G. Thulin, ‘Bag with handle of weldable plastic material’, Google Patents, 27 April 1965: https://patents.google.com/patent/US3180557A/en.

[3] Dagens Nyheter, 9 Oct. 1965: 17.

[4] Dagens Nyheter, 6 Oct. 1975: 37.

[5] Nord-emballage, 6 1974: 51.

[6] I. Martenius, Systembolaget: Ett svenskt kulturarv (Gothenburg: Arkipelag, 2010).

[7] Dagens Nyheter, 26 April 1967: 16.

[8] A.M. Hagerfors, Dagens Nyheter 25 Sept. 1987: 1,7.

[9] Image gallery showing the development of Systembolaget’s bags from the 1960s: https://systembolagethistoria.se/systempasenbildgalleri/.

[10] J. Hagberg, ‘Agencing practices: a historical exploration of shopping bags’, Consumption Markets & Culture 19 (1) (2016): 111–32.

[11] A.M. Hagerfors, Dagens Nyheter, 25 Sept. 1987.

[12] Svenska Dagbladet, 28 Oct. 2005.

[13] L. Valtin-Erwin, ‘A bag for all systems: Historicizing shopping bags in Eastern European consumer culture, 1980–2000’, Journal of Contemporary History 57 (1) (2022): 171–72.

[14] Ibid., 161.

[15] S. Laskow, ‘How the plastic bag became so popular’, The Atlantic, 10 Oct. 2014.

[16] UNEP, ‘From birth to ban: A history of the plastic shopping bag’, UN Environment Programme, 2021: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/birth-ban-history-plastic-shopping-bag.

[17] C. Jordan, ‘Midway: Message from the gyre’, 2009: https://prix.pictet.com/cycles/growth/chris-jordan

[18] K.O. Knausgaard, Autumn (New York: Random House, 2017), p. 11.

[19] Svenska Dagbladet, 2 Feb. 2017.

[20] G. Hawkins, ‘More-than-human politics: The case of plastic bags’, Australian Humanities Review 46 (2009): 41.

[21] UNEP, Legal Limits on Single-Use Plastics and Microplastics: A Global Review of National Laws and Regulations (Nairobi: UN Environment Programme, 2018), p. 12.

[22] Vi 49 (1972).