In this blog, Claudia Leal contextualises her new article in Environment and History, Tenacious: An Alternative History of Dogs (online first October 2025), which aims to contribute to the broader history of human–dog relationships from a new perspective, that of ‘the tropical Andes, rather than the cradle of empire’.

Last night, I woke up at 3:30 am because our building was shaking from an earth tremor. Shawn, my husband, and Atenea, our dog, seemed completely unaware. Atenea had already snuck onto the bed, before she is allowed to, around 5 a.m., shortly before we get up. Rosita, our previous dog, never enjoyed that privilege, even though she was much smaller –a schnauzer-poodle mix, unlike Atenea, who as a muscular boxer-pitbull is admired by the men who exercise in our neighbourhood park.

Just as Atenea and Rosita have shaped my own life, dogs profoundly mould those of so many others across the world. They also influence our sensibilities towards (certain) animals and even the very ideas of what animals are and ought to be. Plus, they are everywhere, in cities and countryside, in mountains and in plains. Historical works on dogs have done a wonderful job in explaining the relationship that predominates among those who write and read such histories: the one that derives from creating breeds and turning dogs into pets. This relationship – marked by leashes, collars and picking up poop – is remarkably recent, a mere blink in the millennia-long partnership between humans and dogs. These histories show how a dog fancy emerged in Victorian England and other industrialising countries, producing a multitude of standardised breeds from the few types that existed (such as hounds and mastiffs), and inviting them to live within the home.

These dogs replaced non-standardised animals that roamed the streets. The flip side of welcoming elegant dogs of all shapes, colours and sizes into our families was the elimination of the ‘undesirable’ creatures whowere seen as polluting the urban environment or who violated our newly-acquired conviction of the proper place of dogs in society. Labelled strays and curs, these dogs were captured and killed, and in some cases adopted, forced to trade freedom for food, shelter and love.

Although many assume this transition is all but complete, places such as Cairo – where dogs are far more common in the streets than in homes – and even my own Bogotá – where pets are widespread – show a different picture. These non-descript animals remain the majority of the world canine population, as they have always been. Their history, therefore, cannot be reduced to one of slow disappearance.

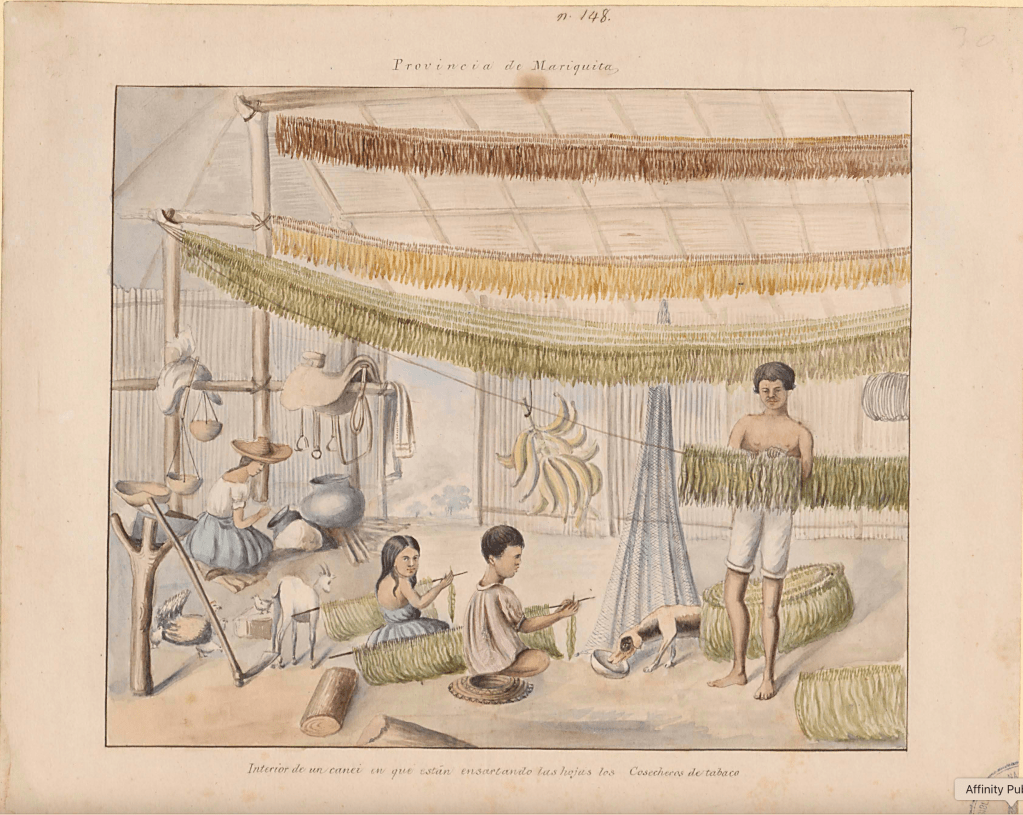

‘Tenacious: An Alternative History of Dogs’ is my attempt to contribute to this broader history from my place in the world – the tropical Andes, rather than the cradle of empire. It draws from a variety of eclectic sources that include studies based on DNA analysis, chroniclers of Conquest, novels, travellers’ accounts, photographs and watercolours, magazines and newspapers. It tells three interconnected stories that span five centuries and move across multiple scales. It begins by reconstructing how Latin American common dogs emerged from the mixing, in the sixteenth century, of colonisers’ dogs with the natives, who descended from those that crossed the Bering Strait with the very first human dwellers of the Americas. Those natives – some mute or bald, many praised as food – virtually disappeared. The new common dogs, who expanded their range and took advantages of newly available niches, especially cities, held a lowly status vis-à-vis the specialised Europeans – hounds, mastiffs and toy dogs.

Their lowly status was captured, in parts of the region and from the 16th through the 20th century, by a word I learned as a child: gozque. In the rural and relatively poor society that Colombia was in the 19th century, mangy gozques populated the country’s varied geography, where forests and jungles predominate. Hunting – to eat, enjoy and boast – was ubiquitous, so dogs that proved skilled at cornering and killing prey achieved an elevated standing. Their courage and might set them apart from the majority of commoners, who kept some people company, annoyed others and filled the sonic landscape with their barking. Distinction was not a matter of pedigree or looks, but of ability and performance.

The article ends by turning to the second half of the twentieth century and zooming in on Bogotá, a city that finally caught up with the dog fancy. As the city expanded rapidly, breed dogs were imported in growing numbers and dog culling became increasingly institutionalised. Veterinary clinics multiplied as families across the social spectrum adopted pets. Yet most of them were – and still are – common dogs who changed living quarters and conditions. In this context, a serious attempt was made to vindicate them by creating a much-desired national breed from the supposedly quintessential gozque. It failed, but a far more effective popular vindication followed. I won’t reveal it here; for that you’ll need to read the article, which I hope you will both take pleasure in and learn from. It is a tribute to my father, who, as Cuban writer Leonardo Padura would say, was a man que amaba los perros.