Today’s blog by Björn Billing introduces his recent article in Environment and History (online first, December 2025), Visualising Icebergs: Early Modern Depictions, ca 1570–1770 and shows how early illustrations of icebergs and glaciers testify to the dramatic impacts of climate change over the centuries.

A23a is on the move again. This iceberg has been drifting and breaking up in stages since it separated from Antarctica in 1986. Although it has diminished during its journey, A23a remains a megaberg, currently about twice the size of Greater London.

An icy behemoth from the deep past, a mysterious planetary traveller, doomed to dissolve in ever-warmer waters – such was the prevailing narrative when the renewed movement of A23a made headlines earlier this year.

Media coverage of the climate crisis frequently foregrounds the planet’s vast ice formations – glaciers, icebergs and the polar ice caps – and public understanding of these frozen landscapes is shaped to a considerable degree by such representations.

However, the mediatisation of polar ice long predates contemporary climate discourse; it has a cultural history, articulated through travel accounts and scientific reports, engraved illustrations and artworks, journalism and fiction, rhetoric and aesthetics.

There is no shortage of excellent studies on this subject, but most of this research focuses on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. How, then, were icebergs visualised and conceptualised in the early modern period? This is the question I explore in my article.

For Europeans in the early modern period, the Arctic was largely terra incognita: blank spaces on the maps but also a natural environment imbued with scientific unknowns. And the most striking and puzzling element in these latitudes was the polar ice. Icebergs constitute ‘one of the greates curiosities in nature’, according to A Concise System of Geography(1800), echoing numerous accounts from polar travellers since the sixteenth century.

Some of the uncertainties concerning polar ice are reflected linguistically in these travelogues. The word ‘iceberg’ did not appear in the English language until 1773, and it remained a rarity for several decades. Instead, explorers wrote about ‘ice-islands’, ‘ice hills’, ‘floating rocks’, ‘islands of ice’, etc.

Furthermore, floating polar ice was not conceptually distinguished from the immense glaciers that sailors encountered in Greenland and Spitsbergen. The rhetoric used to describe the ice suggests that it belonged to the realm of natural wonders, mirabilia. Adjectives such as monstruous, marvellous, strange, rare and peculiar, are common in the reports of polar ice from this period. But it seemed like words alone failed to communicate the appearance of these strange objects in the cold, white regions of the Earth.

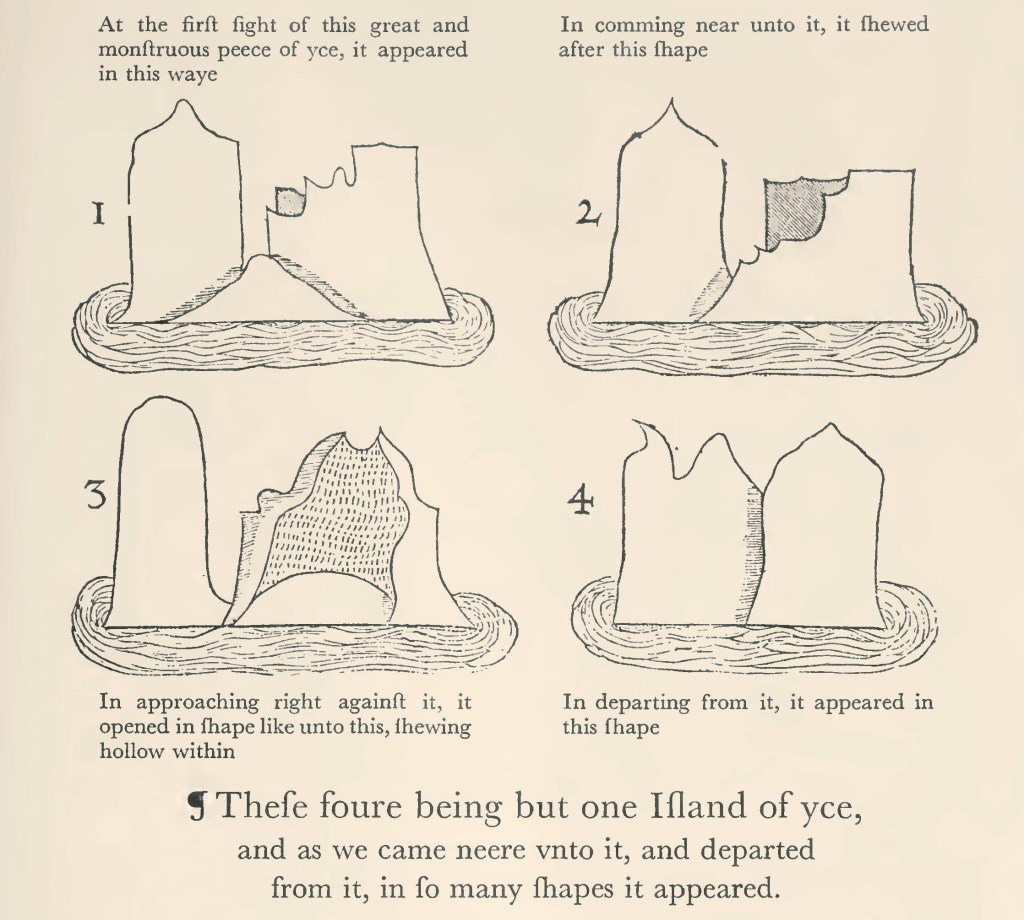

One of the earliest depictions of an iceberg appears in a travelogue recounting Martin Frobisher’s third Arctic voyage in 1578. The author, Thomas Ellis, reported ‘a maruellous huge mountaine of yce’, and supplemented his description with a series of four drawings – this iceberg was so large and visually complex that a single image could not suffice to convey an adequate representation.

With this set of images, Ellis suggested both a mobile observer and an object whose appearance altered significantly with shifting perspectives. In a sense, he thus invited the reader/viewer to become a co-traveller, a virtual witness of the sequential event.

Two centuries would pass before another singular, specific ‘iceberg’ was depicted in an Arctic travel account. The image, entitled View of an Iceberg, appeared in the report of Constantine Phipps’s expedition towards the North Pole in 1773.

Today we would call it a glacier, but Phipps described this massive body of ice in northwest Spitsbergen as ‘one of the most remarkable Icebergs in this country’, and summarised this particular vista as ‘a very romantick and uncommon picture.’

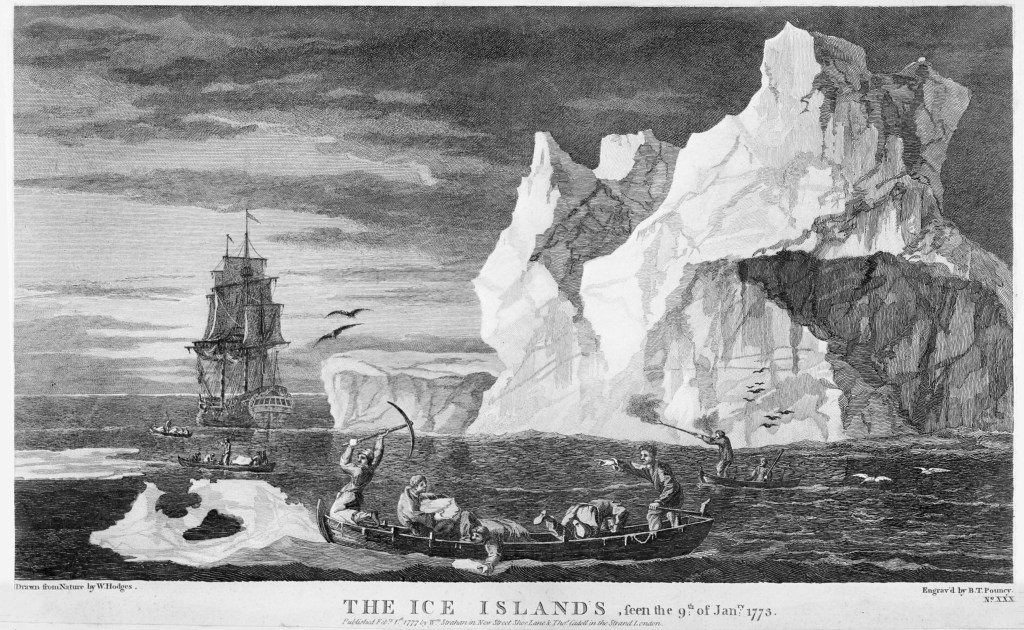

The artist behind this illustration was John Cleveley Jnr. The fact that Phipps employed a renowed artist indicates the priority given to visual representations in exploration accounts in the late eighteenth century. Consequently, James Cook hired William Hodges for his second journey, 1772–1775. Cook’s A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World (1777) includes an illustration of icebergs from Antarctica, produced by Hodges, titled The Ice Islands.

This practice mirrors a wider epistemological discourse. In 1774, the Scottish anatomist William Hunter claimed that an image ‘conveys clearer ideas of most natural objects, than words can express’. Images were integral to the emerging paradigm of empirical observation. The Royal Navy accordingly required its officers to possess basic skills in draughtsmanship.

The illustrations by Cleveley and Hodges are situated in this confluence of exploration, science and visual culture. Cleveley’s work is particularily interesting since it was copied by several artists to be included in books on geography. It also served as a reference by explorers in the early nineteenth century, who visited the specific location in Spitsbergen where the original drawing had been made, on 18 August 1773.

View of an Iceberg is arguably the first illustration of polar ice to have had such cultural and scientific resonance. It appears as one of the most significant Arctic landscape depictions in early modern history, before the era inaugurated by the British expedition of 1818, which marked a new chapter in the visual culture of the Arctic.

Thanks to the skilled hand of Cleveley and the meticulous information given by Phipps, we may ascertain that the depicted ‘iceberg’ is the glacier now known as Frambreen. Today, the illustration bears witness to climate change in the Arctic. A satellite image of this region of Spitsbergen, with superimposed graphics indicating the draughtsman’s vantage point and line of sight towards Frambreen, reveals how significantly the glacier has retreated. The massive wall of ice depicted in Cleveley’s painting no longer aligns with the coastline but has receded deep into the valley.