In this blog, first published as a ‘Snapshot’ in Environment and History (November 2025) Eliot Fackler shows how the histories of western Lake Erie and the Black Swamp provide lessons from Indigenous land-use practices which might offer new ways of addressing current environmental challenges.

On 2 August 2014, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and public health officials placed Toledo, Ohio, residents under a ‘do not drink’ advisory. The previous night, chemists detected the toxin microcystin – produced by Microcystis and other blue-green algae during cell death – near the Lake Erie intake of the city’s largest water treatment facility. Over the next two days, half a million people in metropolitan Toledo could not consume tap water as the liver-damaging poison floated around the mouth of the Maumee River. Ohio’s governor declared a state of emergency. Bottled water sold out of stores. Residents queued up at fire stations as the Ohio National Guard delivered 125,000 litres of water. Some people drove outside the region to avoid lines. Seeking to reassure the public while acknowledging the enormity of the problem, Toledo’s Mayor, D. Michael Collins, offered a contradictory assessment: ‘I don’t believe we’ll ever be back to normal. But this is not going to be our new normal. We’re going to fix this.’[1] By 5 August, microcystin levels returned to normal, and officials lifted the water ban. Yet, the question remained: what long-term fix did officials like Collins have in mind?

Since World War II, western Lake Erie’s tributary rivers have been polluted with fertiliser runoff from commercial farming operations and, to a lesser extent, polyphosphate-containing detergents from waste streams. Beginning in the 1960s, the lake experienced annual Microcystis growth. Over the next five decades, increased runoff and higher lake temperatures caused by climate change intensified algae blooms and depleted the lake’s dissolved oxygen. As the problem worsened, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration began monitoring algal growth. The agency’s 2014 forecast predicted Lake Erie might see its largest bloom ever.[2] That August, Toledo residents became the latest frontline victims of the hijacking of Earth’s biogeochemical cycles.

Since 2014, government agencies, scientists and concerned citizens have implemented various plans to reduce nutrient runoff. Programmes to manage fertiliser, projects re-establishing portions of a 400,000-hectare wetland known as the Black Swamp, and a ballot referendum creating a legal means of protecting the lake have all attempted to return western Lake Erie, its wetlands and its watersheds to progressively earlier moments in the region’s environmental history. Each effort has revealed the long-term impacts of past socioecological changes. This essay briefly describes these attempts to address Lake Erie’s algal blooms and the histories they expose. I contend that the origin of the crisis can be found in the colonial occupation and forced removal of the region’s Indigenous communities in the nineteenth century.

Fertiliser Regulation

Between 2010 and 2020, Ohio spent $815 million to address algae blooms, nearly seventy per cent of the US total. The Ohio Department of Agriculture’s H2Ohio programme, which supports farmers seeking to reduce fertiliser runoff in the Maumee watershed, has been a centerpiece of the state’s post-2014 response. During the programme’s first five years, about 3,000 growers applied for conservation funding covering 810,000 hectares. Additionally, Ohio State University has offered farmers fertiliser applicator training and certification. Most significantly, a 2015 state law seeks to ameliorate more than half a century of nutrient loading by regulating fertiliser usage.[3]

Farmers face significant challenges. Many carry substantial debt and rely on subsidies and crop insurance, especially as seasonal precipitation has become less predictable and more severe. Most growers remain locked in the get-big-or-get-out schema enshrined in US agricultural policy since the 1970s. Nutrient throughputs may temporarily offset underlying problems of declining soil fertility caused by more than a century of monocropping and compaction from heavy machinery. Farmers cannot effectively steward the land and waterways if aggressive fertiliser use remains the surest way to maintain short-term productivity in a heavily capitalised industrial food system.

Wetland Restoration

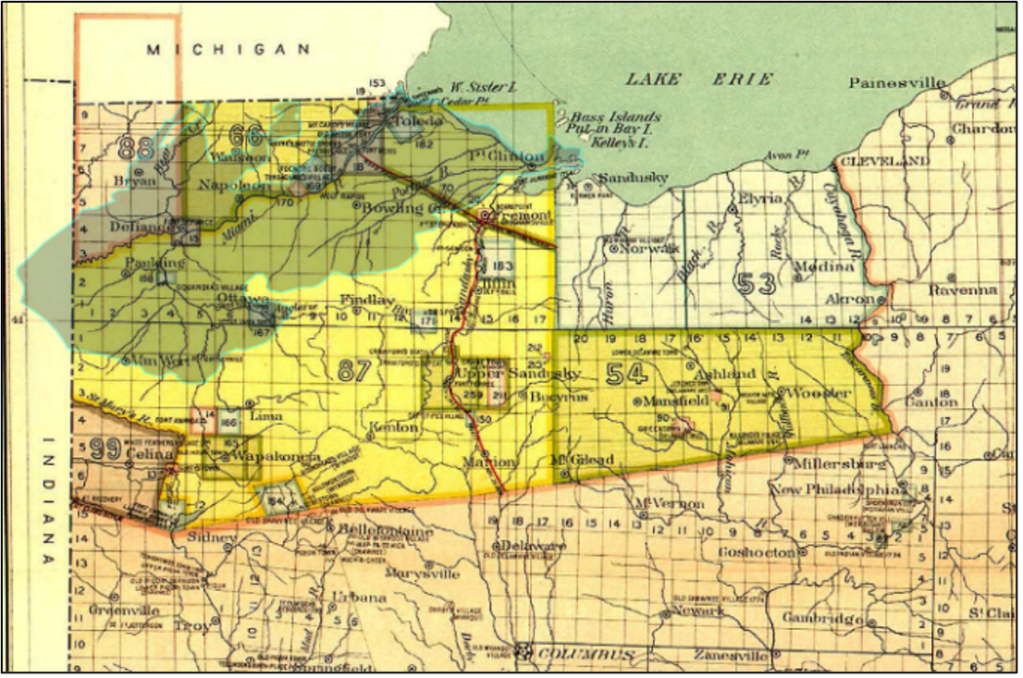

Over the past decade, biologists have sought to protect Lake Erie by restoring nutrient-absorbing wetlands along the littoral. Research teams are attempting to bring back remnants of the Black Swamp, a vast landscape of marshes, hardwood forests and wet prairies that once stretched from Fort Wayne, Indiana, to Lake Erie.[4] Covering much of the Maumee and Sandusky River valleys, the swamp filtered water flowing into the lake from watersheds draining 2.1 million hectares.

American settlers drained the Black Swamp over the nineteenth century. Beginning in the 1820s, newly arrived farmers girdled trees, laid plank field tiles, and brought virgin soil into cultivation. In the 1850s, townships, counties, and the state legislature began funding reclamation projects, paying labourers to channelise streams and dig ditches.[5] During the next thirty years, timber companies clear-cut the ancient elm-ash forests. In a generation, the Black Swamp vanished. With no wetland to absorb nutrients, rain washed topsoil, manure and minerals into the tiles, ditches and rivers bound for the lake. Decades later, the rivers annually discharged half a trillion tonnes of runoff containing hundreds of tonnes of fertiliser. The reclamation era affected the regional ecosystem as profoundly as pollution and nutrient loading would after 1945.[6]

The Rights of Nature

Perhaps the most encouraging, though short-lived, development since 2014 has been Toledo’s passage of the Lake Erie Bill of Rights (LEBOR) in February 2019.[7] The bill ‘establishes irrevocable rights for the Lake Erie Ecosystem to exist, flourish and naturally evolve, a right to a healthy environment for the residents of Toledo, and which elevates the rights of the community and its natural environment over powers claimed by certain corporations.’ LEBOR possessed an enforcement mechanism that distributed responsibility for the lake and the right to speak for it among citizens: ‘The City of Toledo, or any resident of the City, may enforce the rights and prohibitions of this law through an action brought in the Lucas County Court of Common Pleas, General Division.’[8] The bill’s advocates hoped to bring Lake Erie firmly into political decision-making. If enforced, the law would make the environmental, economic and public health consequences of agricultural activities subject to scrutiny by a more capacious body politic, highlighting how local communities are embedded in fragile ecosystems.

Unsurprisingly, LEBOR faced immediate challenges. Opponents were not the Toledoans who had struggled to find drinking water but farmers living upriver and outside the city’s jurisdiction. One farmer’s lawsuit argued that LEBOR was unenforceable and preventing fertiliser runoff was impossible.[9] A federal judge struck down the law, stating it was ‘unconstitutionally vague and exceeds the power of municipal government in Ohio’.[10]

Nevertheless, LEBOR challenged the individualist underpinnings of Western jurisprudence. The bill opened the possibility that the existential interests of the lake, tributary rivers, walleye, coastal marshes, farmers, commercial fisheries and parched city dwellers could all become central matters of concern in a representative democracy.[11] Had LEBOR withstood the lawsuit, citizens could have represented the lake in court and held polluters to account. Like Black Swamp restoration and programmes managing fertiliser usage, LEBOR recalled an earlier moment in the region’s past. By granting the lake legal standing, supporters evoked Indigenous practices that acknowledge humans as responsible members of larger multispecies communities.[12] In this respect, the bill suggests that Lake Erie’s algae problems and the destruction of the Black Swamp are linked to the dispossession of the region’s Indigenous peoples two centuries ago.

Between the 1730s and 1790s, Odawa, Miami and other Great Lakes tribes established villages at the edges of the Black Swamp. They harvested wetland flora and the region’s fur-bearing game. Accumulated food surpluses, wealth from the fur trade and geographical knowledge allowed communities to defend against colonial assaults.[13] When settler violence consumed the Ohio Valley during the American Revolution, Black Swamp inhabitants sheltered displaced Shawnees, Delawares and Munsees, and routed an American invasion force. During the 1790s, a confederacy led by Miami leader Mihšihkinaahkwa won military victories against the United States before losing the Battle of Fallen Timbers. In the subsequent Treaty of Greenville, Indigenous leaders ceded three-quarters of the Ohio Country to the United States but maintained control of the region surrounding the wetland. Further settler invasions and resistance during the War of 1812 resulted in defeat and capitulation. Tribal negotiators signed the 1817 Treaty of Fort Meigs, relinquishing Northwest Ohio to the United States and establishing small reservations around the Black Swamp. The wetland remained a bulwark against complete dispossession, as endemic malaria and impenetrable marshes held most potential settlers at bay. After the Indian Removal Act, federal officials negotiated final land cessions. By 1843, Ohio’s Indigenous communities had been deported west of the Mississippi River, leaving behind their Great Lakes homelands.

From the 1730s to the 1810s, Indigenous communities constructed niches along the Black Swamp’s borders. The wetland provided a refuge for game animals, edible plants, rich soils and a barrier to Euro-American settlement. Because their cultural practices were rooted in animism, seasonal mobility, extensive land use and collective ownership, the Indigenous communities utilised the wetland without engaging in large-scale ecological transformation. Dispossession and the subsequent growth of settler communities inaugurated unprecedented changes.

Since the 1840s, private property, commercial agriculture and industry have remade the landscape and endangered those who depend on Lake Erie’s freshwater. The world of toxic algae blooms, species extinction and global warming was built by the extirpative violence of colonialism as much as anything else. As recently as 2007, the Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma explicitly linked their removal to the lake’s later environmental problems when they unsuccessfully sued the Ohio Department of Natural Resources for fishing and hunting rights in the region.[14] Settler colonialism displaced communities and reoriented the region to commercial agriculture.

The histories of western Lake Erie and the Black Swamp suggest that the lessons of Indigenous land-use practices and an honest reckoning with the lasting effects of colonialism might offer new ways of addressing current environmental challenges. Perhaps mending relationships between the descendants of displaced Indigenous communities, contemporary settler populations and the former Black Swamp should be the first step.

[1] Tom Henry, ‘Water crisis grips hundreds of thousands in Toledo area, state of emergency declared’, Toledo Blade, 3 Aug. 2014: https://www.toledoblade.com/local/2014/08/03/Water-crisis-grips-area.html (accessed 31 March 2025).

[2] NOAA Harmful Algal Blooms Forecast 2014: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9xRuZuOk9wI (accessed 31 March 2025).

[3] Anne Schechinger, ‘The high cost of algae blooms in U.S. water’, Environmental Working Group, 26 Aug. 2020:https://www.ewg.org/research/high-cost-of-algae-blooms (accessed 31 March 2025); Lester Graham, ‘MI and OH: Different strategies to reduce Lake Erie nutrient pollution’, Great Lakes Now, 18 Nov. 2024: https://www.greatlakesnow.org/2024/11/mi-and-oh-different-strategies-to-reduce-lake-erie-nutrient-pollution/ (accessed 3 April 2025).

[4] Tom Henry, ‘Researcher says Great Black Swamp Experiment could help Lake Erie’, Toledo Blade, 28 July 2019: https://www.toledoblade.com/local/environment/2019/07/28/great-black-swamp-lake-erie-experiment-drainage-marshland-again-study/stories/20190728005 (accessed 31 March 2025).

[5] ‘Swamp land notice’, Perrysburg Journal, 16 Jan. 1854, 6; ‘Draining swamp lands’, Ohio Cultivator 13 (7) (1 April 1857): 99.

[6] Graham Harris and Richard Vollenweider, ‘Paleolimnological evidence of early eutrophication in Lake Erie’, Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 39 (4) (1982): 618–26.

[7] ‘Ohio city votes to give Lake Erie personhood status over algae blooms,’ The Guardian, 28 Feb. 2019: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/feb/28/toledo-lake-erie-personhood-status-bill-of-rights-algae-bloom (accessed 3 April 2025).

[8] Lake Erie Bill of Rights: https://www.utoledo.edu/law/academics/ligl/pdf/2019/Lake-Erie-Bill-of-Rights-GLWC-2019.pdf (accessed 2 April 2025).

[9] Jason Daley, ‘Toledo, Ohio, just granted Lake Erie the same legal rights as people’, Smithsonian Magazine, 1 March 2019: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/toledo-ohio-just-granted-lake-erie-same-legal-rights-people-180971603/ (accessed 31 March 2025).

[10] Tyler Gillett, ‘Federal judge rules Lake Erie Bill of Rights unconstitutional’, The Jurist, 29 Feb. 2020: https://www.jurist.org/news/2020/02/federal-judge-rules-lake-erie-bill-of-rights-unconstitutional/ (accessed 31 March 2025).

[11] Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

[12] Kyle Powys Whyte, ‘On the role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as a collaborative concept: A philosophical study,’ Ecological Processes 2 (1) (2013): 7.

[13] Eliot Fackler, ‘Domesticating the country: Colonialism and ecological change in the Black Swamp of the Old Northwest’, Ph.D. diss. (University of Illinois at Chicago, 2020); Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indigenous Prosperity and American Conquest: Indian Women of the Ohio River Valley, 1690–1792 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

[14] Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma v. Ohio Department of Natural Resources, 3:05 CV 7272 (N.D. Ohio, 2008), 4.