Today’s blog by Donghyun Woo introduces his recent article in Environment and History (online first, 2026), ‘Squid and Socialists: Power, Nature and the Unruly East Sea in North Korea, 1945–1964’, and discusses what North Korea’s squid history can teach us.

In the summer of 1962, the North Korean state hosted a unique squid-fishing competition for squid in the East Sea. The regime promised ‘certificates of award’ and ‘prizes’ for high-performing fishermen who harvested more than 25 tons of squid in two months.

Nam Chŏng-hwan also joined the competition. As the country’s only known Labor Hero specialising in squid fishing, his past performance (he caught 27 tons of squid in 1961) set a benchmark the regime expected other participants to match. Intriguingly, no follow-up coverage appeared in domestic media, implying that the competition was a failure.

The Netflix drama Squid Game portrays people under South Korean capitalism playing a deadly game. Their motives are clear: they seek a fortune despite lethal consequences. The stakes are enormous (₩45.6 billion, or about £23.1 million). But what drove North Korean fishermen not to play the squid-fishing game? The answer may seem simple, but my article reveals that it is more complicated.

Two layered stories run through my article. One is a historical interaction between North Korean human actors and squid as marine animal actors. As the article reconstructs, decapodiformes prevailed in this interaction, eventually forcing socialists to revise their media strategies. The other concerns more mundane contacts among politicians, scientists and workers, in which the latter two groups deployed different strategies for living under ideology.

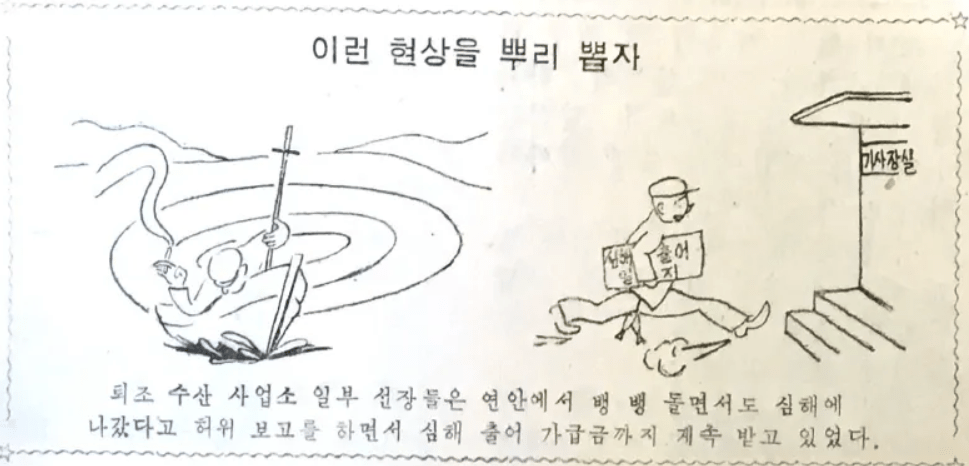

The main message of my article is this: those who live under socialist governance pursue profits (in monetary and other forms) as much as their capitalist counterparts, and this dynamic operated successfully more often than not. As chronicled in my article, politicians in Pyongyang persistently emphasised vigilance in production activities without offering incentives, while scientists crafted narratives claiming that ample catches depended solely on fishermen’s will. In this setting, fishing workers responded by performing the art of ‘going through the motions’; after all, they had no real incentives to catch more squid.

Source: Chosŏn susan 5 (1959): 8.

Even if good incentives had existed, squid fishing would have remained physically demanding and technologically tricky. Each fisheries enterprise in the East Sea, for example, would have had to divert already scarce materials to minimal technological innovations. For what? To meet the quotas, it was far more practical to focus on pollack — much easier to catch than squid — although the regime condemned this practice as ‘speculation’.

When viewed through the lens of profit, it becomes clearer that human actors adapt to their circumstances even in some of the harshest places to live, such as North Korea. It is true that the North Korean regime has utilised highly repressive instruments to control its people. However, it is no less true that North Koreans have also developed strategies to deal with the regime, a point that this story of squid in the East Sea not only enables but also empowers.

What about squid? North Korean ocean scientists reported in 1964 that the decline in squid catches in 1962–1963 was due to weakened warm currents. From squid’s perspectives, the East Sea in those years could be considered less profitable in terms of survival. Squid gliding through East Sea waters thus serve a powerful example of how different forces have co-shaped interactions between human and non-human animal actors in oceanic environments.