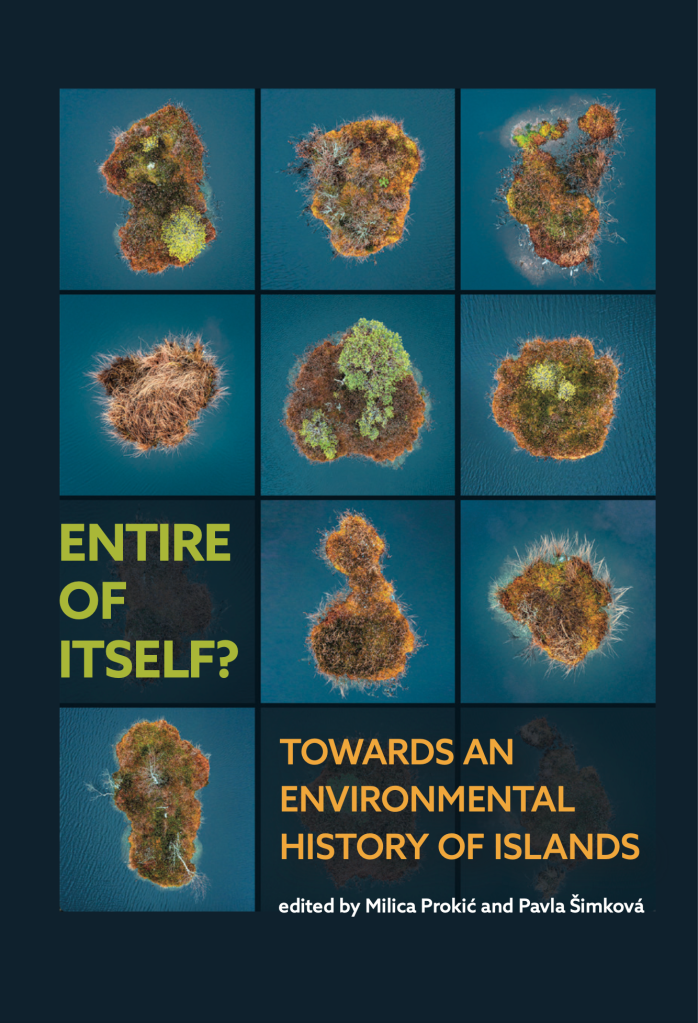

In this blog, Milica Prokić and Pavla Šimková introduce their just published edited volume Entire of Itself? Towards an Environmental History of Islands, which is available in both print and Open Access digital format.

What role has the environment played in the history of islands? Is there even such a thing as environmental history of islands? And if there is, why should we care? These are some of the questions driving our new volume Entire of Itself? Towards an Environmental History of Islands, just published by The White Horse Press. In it, eighteen authors explore the histories of fifteen islands and archipelagos all around the world. The places included in the volume range from remote oceanic islands such as Réunion or the Galápagos to islands defined by their proximity to the coast, such as Gallops Island in Boston Harbor or Nirmal Char, a perpetually shifting mud island in the stream of the Ganga. The chapters span time periods from the second century CE, when the harbour islands of ancient Ephesus were threatened by siltation, to January 2022 when a volcanic eruption destroyed the infant island of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai. From different perspectives, they all probe the way humans and islands have interacted over time.

Entire of Itself argues for islands as a distinct category of analysis within the field of environmental history. We present them as entities whose environmental characteristics make them the perfect sites to study phenomena present elsewhere, but not in such distinctiveness or concentration. We regard islands as concentrative samples of environments, societies and their entanglements; as ‘hotspots’ where different – and often contradictory – ways of human interaction with the environment converge and crystallize.

Island history is a history of vigorous conservation efforts as well as large-scale experimentation and ruthless exploitation. Of the fifteen islands and island groups included in this volume, more than a half currently enjoy some form of nature protection; eight are UNESCO World Heritage or national park sites, or both. Almost all of them are renowned as places of natural beauty and sought-after tourist destinations.

At the same time, however, most of their histories include extreme forms of extraction and environmental transformation. They are places that have been summarily made over to accommodate certain uses; places that have been violently split open to yield valuable resources; and places where new ways of relating to and managing the environment have been tried out, sometimes with disastrous results. The way in which these extreme forms of human interaction with the environment manifests on islands as discrete units of environment makes them a particularly fruitful category of study.

The volume is organised into sections according to three prominent categories of human engagement with islands over time: conservation, exploitation, and experimentation. The choice of these anthropocentric categories is deliberate. The chapters in each section, on the one hand, speak of human ideas, actions, or intentions: to protect, harness, extract from, or experiment with island environments. On the other, the stories told in each of the chapters show that these unique and peculiar environments routinely thwart human expectations. The chapters in each category stress the active role the islands’ environments have played in their histories: shaping, as much as being shaped by, the interactions with humans in unexpected ways.

More than other places, islands capture the imagination, invite identification, and inspire humans to form close relationships to them. The authors of this volume are no exception: while working on our chapters, we caught ourselves more than once referring to the objects of our writing as ‘our’ islands – although none of us hail from ‘their’ islands and some of us have never even set foot on them. For this reason, we decided to include small features that precede each chapter and express this extraordinary degree of identification. They are reflections on the authors’ personal relationships to the islands they write about: variations on a sentiment succinctly summed up by the Tasmanian-born Peter Conrad: ‘Everyone who was not allotted an island of their own at birth seems to have adopted or acquired one.’ These personal accounts tackle the theme of human-island interaction on the individual level, bringing home the idea of humanity’s special kinship with islands.