In this blog, Bo Poulsen reflects on the lost culture of eel fishing, and consumption on Denmark’s Limfjord, as explored in his new co-authored article in Environment and History, ‘Seasonal Migrants and Traditional Ecological Knowledge in a Region of Risk: The Pulse Seine Fisheries in Limfjorden, Denmark, c.1740–1860‘, with Camilla Andersen (ahead of print, October 2024).

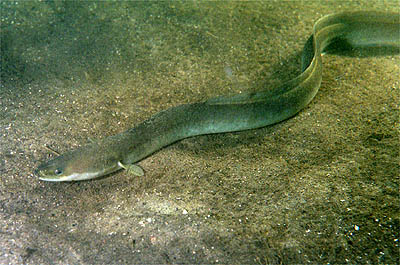

As summer turns to autumn in Denmark’s fjords and sounds, the perpetual twilight zone is replaced by dark nights. This is the signal for the freshwater eels to leave for the Sargasso Sea. This annual mass exodus is countered by young eels that swim in the opposite direction and repopulate Europe’s coastal regions. Each eel makes only one round trip in its life cycle, but with plenty to go around, this peculiar behaviour was once the basis of one of Europe’s most thriving fisheries. Once was, not is.

I grew up in an agricultural area in a small town about twelve kilometres from the part of the Limfjord called Lovns Bredning. As you approached this part of the Limfjord, you were met with a narrow salt marsh before the water. The views from one side of the fjord to the other revealed a world beyond that of an eight-year-old boy. Just ten kilometres further west was the town of Hvalpsund, where many people had summer cottages and where you could swim from a small, natural sandy beach south of the ferry pier. On the pier, an ice cream vendor was waiting for customers in line for the ten-minute crossing to the Salling peninsula.

Further north, at Ertebølle, I also swam with friends as a child. If you go there today, you’ll find it’s much the same as the area where I grew up. From the steep slopes, you can see a large part of the central part of the Limfjord, which glitters silvery in the sunshine. Behind you, you can see the clear outlines of Salling, Fur, Livø and, further away, Mors and Hanherrederne. Some of the last hunter-gatherer peoples in Northern Europe fished in this area. Several thousand years later, archaeologists gave their name to the Ertebølle culture. They had a similar view, but much else has changed. The Limfjord was home to Denmark’s most important eel fishery, and when I was a child in the 1980s, you could get eel anywhere in the area.

In the summer, the many inns along the 750 kilometres of coastline along the Limfjord laid out pans and tables for countless festive and unpretentious eel feasts. Eel is a fatty fish. Cut it into finger-length pieces, toss it in flour and fry it in a rich layer of butter. You get a rich meal. But it was cheap food, and there was plenty of it. As a little boy, I went out to eat eel with my father several times and I remember it clearly: large steel trays of golden fried breaded eel served dripping with fat. The meal also included fresh potatoes with parsley sauce and, for the little boy, an orange soda.

My father and I were newcomers to the area. We observed from the social periphery of our small table, slightly outside the crowd. My father knew best and told me to eat as much as I possibly could; ‘When you’re finished eating, put the skeletal parts of the eel in a row on the edge of your plate and see if they can reach all the way round. That’s the custom. Look around, this is what others do, and it was the same when I was a child. Grandpa could eat so much that the leftovers made it twice round the plate’.

This food was the fuel that kept the hard-working men and women of the region going. I distinctly recall the atmosphere at the inn was particularly uplifting among the other guests, more chatty than the normal reserved nature of people in this area. They were happy about the abundant food, and they were happy about the fact that they could wash down the fatty food with cool lager beer and a snaps, Danish style vodka.

It’s my memory, yes, but it’s also a common heritage for anyone my age or older who grew up in this part of Denmark. Today, however, it is nothing more than a memory. You can still find a few pubs advertising eel, but it’s no longer locally caught eel, because it’s not allowed. For decades, the eel has been an endangered species throughout Europe. The amount of eel fry from the spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea reaching Europe’s coasts, fjords and rivers has fallen by between 90–99 per cent since the 1970s. Consequently, there are now frequent, lengthy bans on eel fishing.

Coauthor of ‘Seasonal Migrants and Traditional Ecological Knowledge in a Region of Risk: The Pulse Seine Fisheries in Limfjorden, Denmark, c.1740–1860’, Camilla Andersen, who lives with her lovely family by the Limfjord, told me about a Last Supper-like atmosphere when she attended a Christmas party a few years ago. As tradition dictates, eel was served, but with a special reverence because after Christmas a total ban came into force that covered both anglers and commercial eel fishing.

This part of Denmark is still full of memories of eel fishing. Migrant fishermen from Harboeøre and Agger parishes in the far west between the North Sea and the Limfjord were renowned for their eel fishing abilities. Each summer, they sailed into the fjord and stayed for two months with local farmers. In exchange for fresh eels, they were permitted to lodge with the farmers and bring their nets ashore while they fished for eels with pulse seines in the fjord’s twilight.

Pulse seine fishing was a unique fishing method in Danish and possibly international fishing history. The method, which was primarily practised in the Limfjord, required two boats and four men. One boat sailed a fine-meshed net, a seine, out in a semicircle connected to the other boat, which held the other end of the seine. Then, a club shaped like a bell at the bottom, was hurled, or ‘pulsed’ into the water. The pulsing caused a resounding bang and sent downward air bubbles in the water, which scared the fish into the seine. The fishermen then pulled the seine up between the boats and hauled the eels over the rail.

Many museums around the fjord have gear on display, and in several places along the fjord, you can still see jetty sites with clear traces of the tar and machinery used for dipping fishermen’s nets in liquid tar to increase their durability. Furthermore, there are accounts of conflicts between the local fishermen of the Limfjord and those who had migrated there. The best-selling novel in Denmark in the twentieth century was Hans Kirk’s The Fishermen (1928). It is about a clash of cultures between travelling fishermen from the North Sea coast and the original inhabitants of the island of Gjøl in the Limfjord.

But, who were the travelling sea dwellers from the North Sea coast? In our article, we uncover how pulse seine fishing developed, why the fishermen got into a rare fight, and why the practice is closely linked to the natural resources of both the Limfjord and the Limfjord bar in the North Sea.